WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

First off, as a way of further honoring the recently opened blockbuster Vermeer retrospective at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, another dive into the Archives for yet another of Ren’s takes on the Delft master. And then, a wry Convergence, looking back at the incomparable Nicolas Slonimsky’s travails as an immigrant music teacher in Boston in the thirties and then forward into the musical stylings of our possible future chatbox overlords.

* * *

From the Archives

A GIRL INTENT:

SZYMBORSKA AND THE LACEMAKER

MAYBE ALL THIS

by Wislawa SzymborskaMaybe all this

is happening in some lab?

Under one lamp by day

and billions by night?Maybe we're experimental generations?

Poured from one vial to the next,

shaken in test tubes,

not scrutinized by eyes alone,

each of us separately

plucked up by tweezers in the end?Or maybe it's more like this:

No interference?

The changes occur on their own

according to plan?

The graph's needle slowly etches

in predictable zigzags?Maybe thus far we aren't of much interest?

The control monitors aren't usually plugged in?

Only for wars, preferably large ones,

for the odd ascent above our clump of Earth,

for major migrations from point A to B?Maybe just the opposite:

They've got a taste for trivia up there?

Look! on the big screen a little girl

is sewing a button on her sleeve.

The radar shrieks,

the staff comes at a run.

What a darling little being

with its tiny heart beating inside it!

How sweet, its solemn

threading of the needle!

Someone cries enraptured:

Get the Boss,

tell him he's got to see this for himself!translated by Stanislaw Baranczak and Claire Cavanagh

"In my dream," Wislawa Szymborska had written in a slightly earlier poem ("In Praise of Dreams," 1986), "I paint like Vermeer of Delft." And in this poem she paints like him as well. Surely, at any rate, the image splayed across the cosmic screen in the last stanza of "Maybe All This" (1993), the picture Szymborska's words have in mind must be something very like Vermeer's Lacemaker. How marvelously, at any rate, the poem helps elucidate the painting, and vice versa.

Start, perhaps, with the painting (created in Delft, around 1674): how everything in it is slightly out of focus, either too close or too far, except for the very thing the girl herself is focusing upon, the two strands of thread pulled taut in her hands, the locus of all her labors. This painting is all about concentration: gradually, spiralingly, we come to concentrate on the very thing the girl herself is concentrating on (everything else receding to the periphery of our awareness), like nothing so much as a painter lavishing his entire attention on his subject (or else, perhaps, like what happens as we ourselves subsequently pause, dumbstruck, before his canvas in the midst of our museum walk).

Are we perhaps exaggerating here? Look more closely at the threads themselves, how they arrange themselves into a crisp, tight V, couched in the M-like cast of shade and light playing upon the hand and fingers behind them. The girl, godlike, momentarily focuses all her attention onto VM, the very author of her existence.

And hence back to the poem. For the girl threading her needle, "the darling little being with its tiny beating heart inside," is of course none other than the poet herself, intent over her page, laboring toward the perfected line (or else, subsequently perhaps, we, her readers, hunched over her completed poem). Though, as creator of the poem, Szymborska is of course simultaneously the Boss (as do we, too, the poem's readers, momentarily get to be, re-creating, recapitulating her epiphanic insight, seeing it clean for ourselves).

Indeed, Szymborska gets it just right; how in the perfected work of art (be it a poem or a painting), across that endlessly extended split second of concentrated attention, artist and audience alike partake of a doubled awareness: the expansive vantage (lucidly equipoised) of God, the concentrated experience (meltingly empathic) of his must humble subject.

*

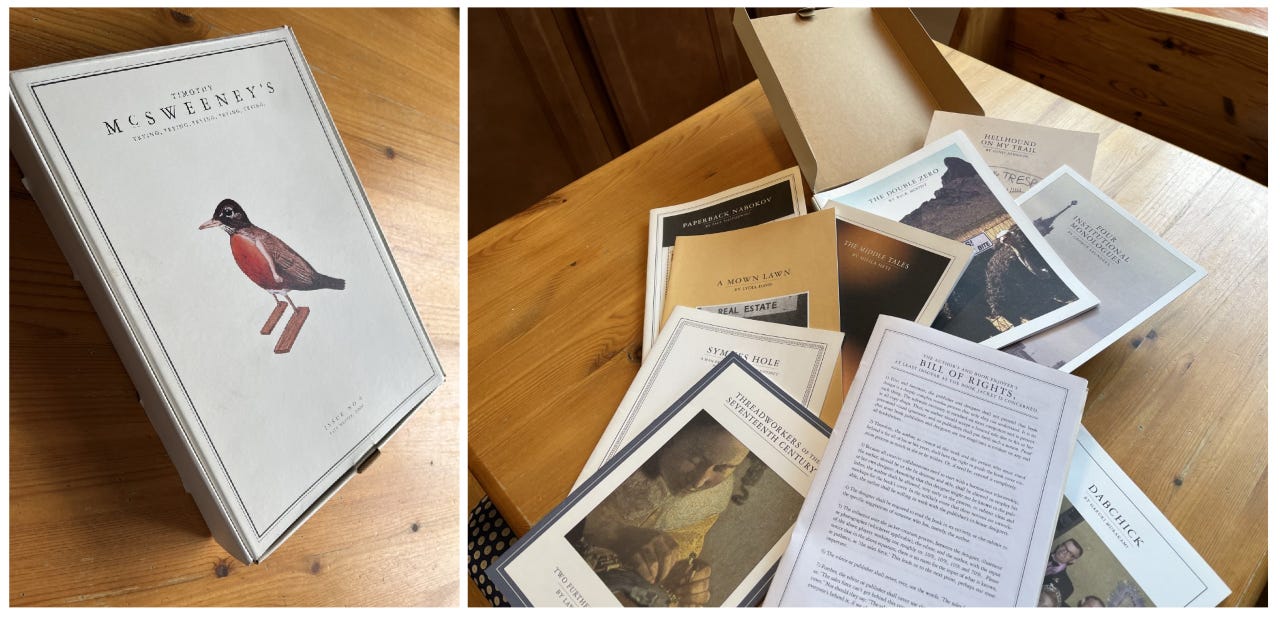

That piece first appeared in its own separate pamphlet in McSweeney’s #4 of late winter 2000, the issue that came in a box where each contributor got their own booklet, whose cover they themselves got to design.

(Dave Eggers, our intrepid leader, was engaged in a battle over the right of authors to determine their own cover art, independent of the desires of the sales force or any other such would-be stakeholders, vis-a-vis the cover of his own then-imminent first book, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius and even included a manifesto on the subject in the box.) I subsequently included the piece in two of my own books, Vermeer in Bosnia and Everything that Rises, and I’ve long considered it a sort of touchstone to all my work, a sort of summary aspiration. I sometimes consider this entire Substack a sort of lacework project, and for that matter, I wouldn’t mind if the Szymborska poem were to be read at my own funeral when the time comes.

But that sense has become all the more powerful to me in recent weeks as I’ve been working on a new Vermeer piece, which will be out soon (details to follow in due course) because I’ve now grown convinced (the reason for the conviction being of the essence of this new piece) that The Lacemaker painting was Vermeer’s last (in the original versions of this piece I’d given the painting the conventional dating of “around 1669,” which as you will have seen above I’ve now recast as 1674, he would be dead within a year, his life cut bitterly short by a frenzied stroke at age 42. Which somehow lends the Szymborska poem all the more talismanic resonance.

* * *

A TWENTIETH / TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY CONVERGENCE

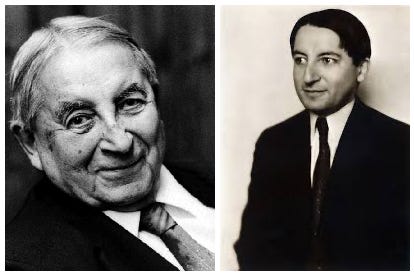

The late great Nicolas Slonimsky, describing how he managed to eke out a living as a relatively new émigré in Boston during the mid-thirties, from my 1986 New Yorker profile of the droll avant garde master conductor and musicologist, subsequently preserved in my Wanderer in the Perfect City collection:

“I charged two dollars a lesson, but I invariably failed to look at my watch—much to the distress, I imagine, of my captive students,” Slonimsky recalls. “Some of them, though, I must say, nearly drove me over the precipice. I had one sixteen-year-old kid for example, who protested vehemently at my assigning him the slow movement of a Mozart sonata, because he felt he wasn’t getting his money’s worth per number of notes played. And then there was the society matron who came to consult with me one day about a symphonic poem she claimed to have conceived. When I asked to see the score, she said no, I didn’t understand—that was precisely where she required my help: to arrange what she heard in her imagination. She proceeded to describe a flat desert, horses galloping in the distance, a rising storm (violins, drums, whatever), the wind subsiding, a full moon rising (perhaps, she suggested, to be represented by a lilting flute)….”

How I wonder what Slonimsky, who finally passed (speaking of the passing of great masters) on Christmas Day in the year 1995 at the age of 101-and-a-half (completely lucid almost to the very last), would have made of this fresh item plucked from the nation’s thrumming digital presses:

From “Google’s AI turns Text into Music,” by Mitchell Clark, at The Verge.com, Jan. 28, 2023:

Google researchers have made an AI that can generate minutes-long musical pieces from text prompts {…} The model is called MusicLM, and while you can’t play around with it for yourself, the company has uploaded a bunch of samples that it produced using the model.

The examples are impressive. {…} Perhaps my favorite is a demo of “story mode,” where the model is basically given a script to morph between prompts. For example this prompt

electronic song played in a videogame (0:00-0:15)

meditation song played next to a river (0:15-0:30)

fire (0:30-0:45)

fireworks (0:45-0:60)

resulted in the audio you can listen to here.

As it turns out, the same folks have been coaxing their chatbot into responding musically to visual prompts—scoring masterpieces of painting, that is—alas to no more bracing effect (at least up until now).

To click on any of the above examples (and, god help us, many others) go here and scroll down to “Painting Caption Conditioning,” which is the fifth section.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford…

…who this week tweets, “See what you can do with this prompt, Google.”

The Animal Mitchell archive .

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

Several balls juggling in mid-air, none of which (mixed metaphor alert!) has quite yet hatched, but don’t worry, we’ll have something swell for you, just you wait and see.

Oh how DARE they let AI mess with music. That’s not writing, it’s stealing and patchwork.