More Breyten

Last week, in the issue of the Cabinet I’d given over to the memory of my dear friend and onetime subject, the great exiled Afrikaner poet/painter/political prisoner & anti-apartheid activist Breyten Breytenbach, who passed away last month in Paris at age 85, I suggested I’d likely have more to offer, and indeed here is some.

For starters, his poetry, the aspect of Breyten’s prodigious production that NPR’s Scott Simon also chose to focus on in the commemoration he offered on his private “Open Book” podcast one evening last week (link here {for some reason you may have to link in, go out, and link in a second time}).

Scott focused on two verses in particular. The first, “Letter from Abroad to Butcher,” Breyten’s slashing indictment of the torture-regime back home, written from Parisian exile in the sixties and addressed to the country’s dread then-security (and eventual prime) minister John Vorster, proved among the stanzas that would get him in so much trouble when he tried to return to the country incognito in the mid-seventies to make contact with fellow oppositionists but instead ended up captured, tried and condemned to prison for over seven years. The second, “Your Letter,” was addressed to his wife Yolande back in Paris from the very bowels of that incarceration.

So much of Breyten’s poetry during the first half of his life was given over to aching nostalgia, while in Paris for his homeland, as in this poem, “The Hand Full of Feathers,“ addressed to his mother, (“Ma / I’ve been thinking / if I ever come home / it will be without warning toward daybreak”) or then, once in prison (from whence he wasn’t even allowed to attend that mother’s dying, as evoked in this poem) for his wife back in Paris, as in this excruciatingly beautiful lyric, the one that was included in braided Afrikaans and English form in the radio documentary I included in last week’s issue, but here is the text:

THE RETURN

in rue Monsieur-le-Prince

coming down the same side

as the Luxembourg gardens, on the left,

where the evening sun burns the small twigs

so as to make its nest in the trees,

the same side as the Odéon theatre

that honeycomb of freedom

as long ago now as May sixty-eightin rue Monsieur-le-Prince

is the restaurant where we will meet

at precisely nine o'clock —

you will recognize me, I'll be wearing a beard once again

even though it may be of cheap silver

and the Algerian boss-cum-cook

with the moustache nesting in his red cheeks

will come and put his arms full of bees around my shoulders

saying

Alors, mon frère — ça fait bien longtemps . . .

should we order couscous mouton for two?

— I can already taste the small snow-yellow grains

and the lump of butter —

and a bottle of pitch dark Sidi Brahim

smacking of the sun and the sea?

and then what would you say to a thé à la menthe

in those flower-decked glasses all scalding wet?

listen to that same wind calling

through the old old Paris streets

”You're the one I love and I'm feeling so good!”

As I discussed last time, while imprisoned, Breytenbach, this supreme colorist, had not only been forbidden to paint but, to the extent possible, he wasn’t even allowed to see colors. When he finally was released and returned to Paris—well, I talked about that in another section of the New Yorker profile I sampled in last week’s issue, (the one included in my Calamities of Exile collection) in this instance at the beginning of part three:

Back in Paris, Breyten tried to retrieve his life, but doing so turned out to be not nearly so simple as ordering couscous mouton for two on the Rue Monsieur-le-Prince. "It can be terribly disrupting being forced out of prison like that, having freedom forced upon you," Breyten explained to me several years later, during our conversations in his Paris studio. "Because it's the opposite of what I was saying the other day about how life inside prison consists of the intensification of experience wrapped inside its mortification. Because now, coming out from that zombified world of prison, I felt I was moving into a different sort of zombified world. It was a complete turnabout. I kept feeling that these people really don't know what life's about. They don't see the colors, they don't hear the sounds. In prison, being woken up at four in the morning and marched through the yard on your way to work, yes, it was dehumanizing, but on occasion you'd look up into the sky and you heard that star—you heard it!—and to an extent you continued in that state of heightened awareness for months after your release. It could get to be too much, of course. There was so much more stimulation on the outside that it got to be physically exhausting, and sometimes I almost longed to be back in my cell."

There was of course one cell to which Breyten needed to return—his painting studio—though for several weeks he kept circling it skittishly. "I was afraid, because I hadn't painted for seven and a half years," he said. "And with painting, as with music, you worry that if you don't practice it, a lot of it goes—a lot of the technical ability. I was really scared in front of that first canvas."

I asked him if he still had that painting. He rummaged around in the back and pulled it out. It was dated "February 1, 1983," and the image, competently rendered in dull grays and browns and blues, consisted of his face in a mirror, bruised and pummeled and haggard, with the eyes closed.

I asked him why he had painted himself with his eyes closed, and he replied, "It was all too tender still. I couldn't look at myself yet." (I've often thought about that answer in the years since, and it has seemed ever more magical: he couldn't look at himself, so he painted a picture of himself with his eyes closed. Who/what in such a situation is looking at whom/what? And who are we, where are we, gazing over the shoulder of that regard?)

The act of painting, however, seemed to draw him out, and to heal him. "There was this richness in just basking in the absolute glory of handling brushes and tubes of paint, simply for their own sake," he told me. "And then, of course, there was the hunger for color itself: color quite apart from what it means or any of its associations, just color as such—the mad, wonderful yowl of it."

And indeed, that passion was to read clear through to the end. Last year, I visited Breyten in his Paris studio once again, and he rifled among a recent series of canvases—alas I only had the wit to capture a bit over a minute of that cavalcade on iPhone video, but here it is:

Link here.

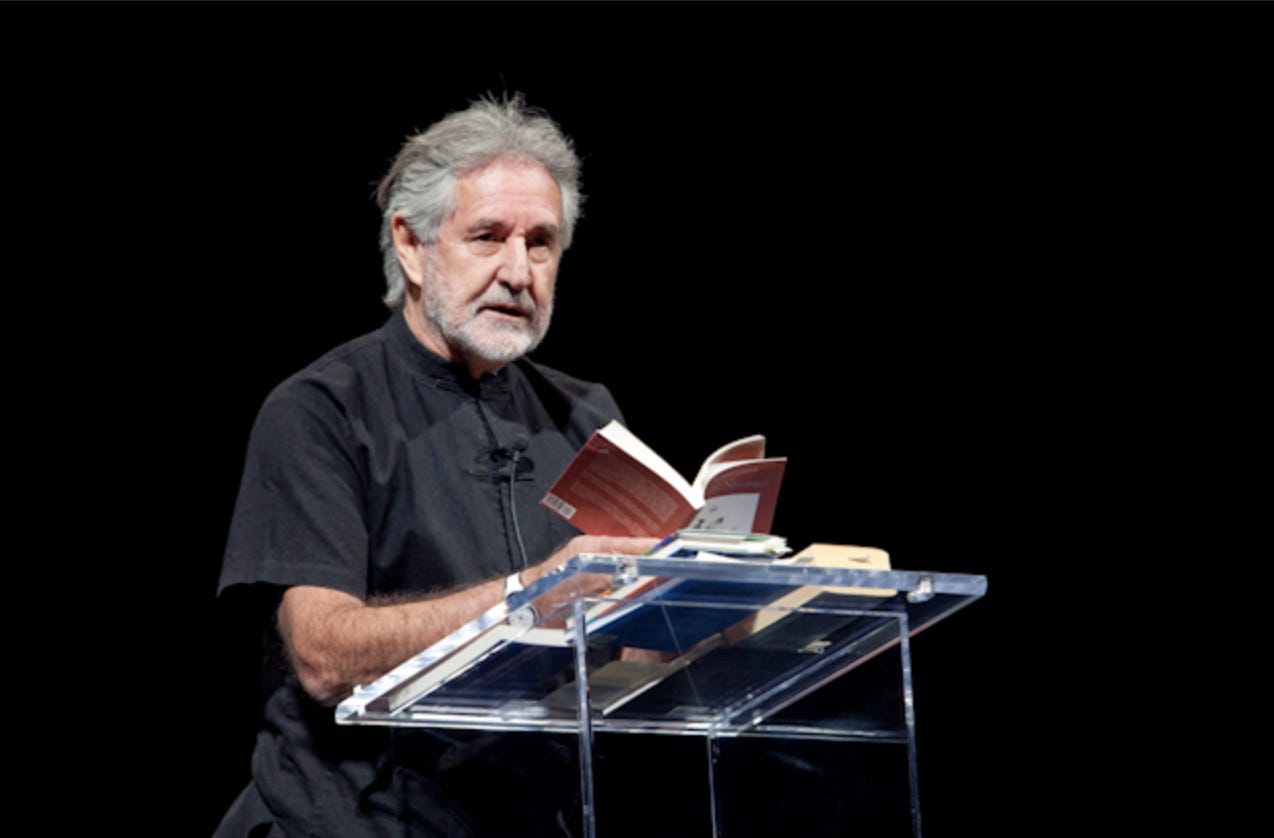

Finally, as I was rifling through my own Breyten files these past few weeks, I also came upon the audio of a reading and public conversation he and I held in 2007 at the Lensic Theater in Santa Fe on the occasion of his receiving a coveted Lannan Literary Award.

As it happens, in the middle section of the evening, Breyten reads from some of the same poems Scott Simon read on his podcast, though it’s odd: I almost prefer Scott’s versions. Not that Breyten’s aren’t obviously commanding, but his voice is so mellow-luscious that sometimes we almost find ourselves, enthralled, slipping away from the meaning of the words. On the other hand, that was hardly the case later on in his presentation, starting around 42:50, when he turned to his (still startlingly pertinent) impressions of a then-recent visit alongside other fellow writers to Gaza and the West Bank and in particular his longtime concurrent friendships with the great Palestinian poet Marwan Darwish and the Israeli master Yehuda Amichai.

Following that, he and I get into our conversation proper, starting around 57:30 and we range far and wide, some of it quite fun and goofy (especially for a few minutes around the one-hour mark, 1:00:00)

but much of it—especially as we conclude with his evaluation of the then-current situation in his anguished homeland, compared once again, at the very end, with that of Palestine—thoroughly suffused with the profoundly humane capaciousness which will remain Breyten’s lasting legacy.

Ah, how we miss him. And how he lingers.

(Turns out Old Mongrel Breyten was a bit of a Jew, as well. You know the one about the difference between the British and the Jews, how the Brits always leave without saying goodbye, whereas the Jews say goodbye without leaving.)

* * *

See you next week!

Thank you for these beautiful memories of Breyten Breytenbach. I met him a few times as I translated three of his books into Italian. I had read True Confessions when I was living in Africa and proposed it to Carla Costa, owner of the Costa & Nolan publishing house (no longer active), who was happy to publish it - and then Memories of Sand and Dust and Return to Paradise. We both remember Breyten as one of the most profound and intelligent people we have known.

Hello Lawrence,

I've appreciated your book Boggs: A Comedy of Values for a number of years, after having seen the documentary of Boggs on PBS. I later purchased a signed copy of your book online.

I also have a copy signed by both you and Boggs, which I obtained from Tom Christie, a (former?) writer for the L.A. Weekly. According to Tom, this book signing happened at a fundraiser for the 'Museum of Jurassic Technology' at the Foshay Masonic Lodge on Venice Boulevard in Los Angeles.

Your inscription reads: "To Tom, Master Spore Shedder."

Boggs' inscription reads: "2–Tom, MJT", which according to Tom Christie is a reference to the above-mentioned 'Museum of Jurassic Technology.' Tom described it as a fun night. Apparently Boggs drew one of his bills there.

Do you happen to know if Boggs signed many other copies of your book? Or was this a 'one-off' situation where both of you just happened to be in the same place at the same time?

Any recollections of that time together would be greatly appreciated. It's a shame Boggs is no longer with us.

Sincerely,

Roger

Windsor, ON Canada