WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

Lech Walesa on the Trump-Zelensky debacle, followed by the first installment of a two-part profile of the artist Ed Kienholz.

***

CURRENT AFFAIRS

Leave it to Poland’s Lech Walesa, one of the greatest heroes behind both Polish Solidarity and the entire eventual downfall of Soviet communism, to come up with perhaps the most trenchant response to Trump and Vance’s shameful tag-team Oval Office takedown of Ukraine’s Volodymir Zelinsky last Friday. You may have heard passing reference to his open letter, but it’s worth sampling the thing itself at some length. So, here you go:

Dear Mr. President,

We watched the report of your conversation with the President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky with horror and distaste. We consider your expectations regarding showing respect and gratitude for the material assistance provided by the United States to Ukraine fighting against Russia to be offensive. Gratitude should be given to the heroic Ukrainian soldiers who shed blood in defense of the values of the free world. They have been dying on the front lines for over 11 years in the name of these values and the independence of their homeland attacked by Putin's Russia.

We do not understand how the leader of a country that is a symbol of the free world can not see this.

We were also horrified by the fact that the atmosphere in the Oval Office during this conversation reminded us of the one we remember well from interrogations by the Security Service and from the courtrooms in communist courts.

Prosecutors and judges, commissioned by the all-powerful communist political police, also explained to us that they held all the cards and we held none. They demanded that we cease our activities, arguing that thousands of innocent people were suffering because of us. They deprived us of our freedom and civil rights because we refused to cooperate with the authorities and did not show them gratitude. We are shocked that you treated President Volodymyr Zelensky in a similar way.

{…} Mr. President, material aid - military and financial - cannot be an equivalent for the blood shed in the name of independence and freedom of Ukraine, Europe, and the entire free world. Human life is priceless, its value cannot be measured in money. Gratitude is due to those who make the sacrifice of blood and freedom. For us, the people of "Solidarity", former political prisoners of the communist regime serving Soviet Russia, this is obvious. We call on the United States to honour the guarantees it and Great Britain gave in the Budapest Memorandum in 1994, which explicitly stipulates a commitment to defend the inviolability of Ukraine's borders in exchange for Ukraine's surrender of its nuclear weapons. These guarantees are unconditional: there is not a word about treating such aid as economic exchange.

The letter was cosigned by almost fifty onetime Polish oppositionists, all of whom had suffered extended stays in prison on behalf of their convictions, including Adam Michnik (who may well have coauthored the note, it bears his distinctive style). You can access the full letter, with the full list (a veritable honor role) of cosigners, here. As a fellow American, all I can say is that it’s a complete and utter Shanda to be on the receiving end of such a letter.

* * *

The Main Event

Folks seemed to enjoy my inclusion of that extended passage about TWA and a Tiffany lamp from my 1975 oral history of artist Ed Kienholz a few weeks back, and it got me to thinking about a profile of him that I subsequently prepared for The New Yorker, just over twenty years later, in 1996, on the occasion of a long-overdue full-scale retrospective of the artist (who had died two years earlier), mounted under the curatorial supervision of his long-ago colleague, the legendary Walter Hopps, at the Whitney in New York. The piece ran at about half its original 12,000-word length, and it occurred to me that, thirty years on from that, it might be fun to show you a director’s cut, which I will hereby be doing in two parts. (Note that the first several paragraphs of Part One recapitulate some of the material covered in that entry two weeks back.)

Of Cars and Carcasses:

A Profile of artist Ed Kienholz

on the occasion of his 1996 retrospective at the Whitney,

parts of which originally ran in The New Yorker, May 5, 1996

PART ONE

The offending vehicle seems almost pastoral now in its fumbling innocence—the squashed, squat blue Dodge with its feverishly groping inhabitants who almost got the L.A. County Museum of Art shut down, precisely thirty years ago this month {coming on sixty years ago now}, on the eve of the opening of Ed Kienholz's first career retrospective. (A new retrospective—only his second in America though there've been countless others abroad in the years since—has just opened at the Whitney, two years after Kienholz's passing.) The artist was thirty-nine at the time and we were all a whole lot younger (and in fact, that show, neatly slotted between the advent of the Beatles and Chicago's Days of Rage, had a good deal to do with forcing everybody to grow up).

The car lay sedately splayed on a beer-bottle-strewn, fake grass pad, its windows meshed over, a young girl's underslip spilling forlornly onto the foreshortened car's front hood, cheap radio music wafting out from inside the cab's closed interior. If you were drawn, despite yourself, to surreptitiously open the car's side door, as clearly it was intended that you be, you were suddenly confronted by a young couple in a rictus clench, the boy (ghostly, transparent, fashioned, as it happened, out of chicken wire) struggling to yank the panties from off the girl's more substantial, spread and prone legs, she struggling either to resist or to accommodate him, or both (it was hard to tell). Leaning in further, you might have noticed how in that moment of their urgent passion, their two heads had melded into one. And just beyond and above that, you might suddenly have noticed a leering voyeur, peering clammily through the far door's window: your very self (as, now, you'd finally realize) cannily mirrored.

County Supervisor Warren Dorn, at any rate, clearly did not like what he saw—or, perhaps, liked it all too well, spying a nice, fat tranche of political opportunity. The Republican state gubernatorial primaries were fast approaching, and the veteran politico now resolved to launch his own candidacy by prodding his fellow supervisors into a lather of puritanical righteousness over the art world's manifestly depraved moral standards as evinced by this and other such pieces in the impending show (notably including a neighboring room-sized tableau called "Roxys," a surrealistic evocation of the seedy wartime parlor room of a Nevada bordello). "My wife knows art," Supervisor Dorn intoned portentously at the news conference kicking off his gubernatorial run. "I know pornography." He issued a slew of dire ultimatums to the Museum's trustees and then, for good measure, had himself photographed slamming the offending car's door resolutely shut.

Clearly, however, he hadn't been counting on the artist himself, who turned out to be quite a serious (if devilishly ironical) moralist in his own right (the car piece's title, "Back Seat Dodge, '38," might have been expected to have afforded the supervisor a clue), and in fact—as the press quickly realized—a charmingly winning public citizen, solid, goateed though otherwise clean-cut, and the single, loving, father of two small children to boot. (A snugly Rockwellian family portrait disconcertingly adorned the catalog's title page.)

Dorn never had a chance. Just for insurance, however, or so he would later claim, Kienholz had bugged his brothel tableau immediately prior to an official inspection tour by a small group of supposedly scandalized supervisors; and just as he'd expected to, he'd managed to capture on tape the wistful, confidentially whispered private recollections the piece succeeded in provoking among these manly men ("Gee, Kenny, look at this, I haven't been in one of these in over twenty years, look at that over there!").

In the event, however, Kienholz never was forced to deploy the tape: even without it the supervisors had unexpectedly become laughing stocks (such was the velocity with which the times, at the time, they were a'changing). The exhibit opened on schedule, virtually without concessions (a guard was posted by the Dodge's closed door, opening it every fifteen minutes, but only on behalf of "appropriate" visitors, an amorphous category which rather quickly swelled to include anyone who happened to be standing there). Someone distributed small yellow "Yes!" buttons to the throngs already lined up outside the museum's gates that first morning (the first of multitudes whose sheer numbers never subsided throughout the rest of the show)—one of the buttons even managed to make its way onto the heaving chest of the backseat girl. Dorn's candidacy went down in flames: instead the Republicans opted for a political novice, an actor named Ronald Reagan.

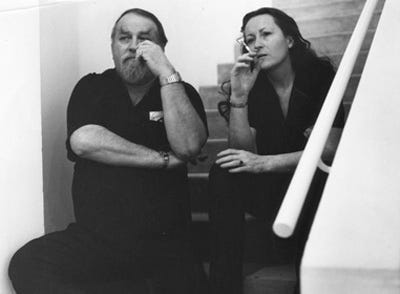

But, as I say, that was a long time ago, and today as the blue Dodge presides demurely in a basement alcove at the Whitney, its door flung wide open and its contents easily visible to any passers-by along the sidewalk above (across the moat), or else to any visitors inside on their way to the museum café, it's hard to see what the fuss was all about—especially when you compare that work with some of the things Kienholz and his wife Nancy perpetrated in more recent years. Ed met Nancy six years after the infamous LACMA show: the fact that she happened to be the only daughter of Tom Reddin, the chief of the L.A. Police Department, must have added a certain impudent piquancy to the attraction, probably in both directions, though clearly, too, there was something special about Nancy, something that allowed this marriage, Ed's fifth (and her second) to grow and deepen and endure for over twenty years, right up till his passing. In 1981, in public recognition of the remarkable way in which their lives had become utterly entwined, Ed announced that henceforth they would cosign all the work emerging from the Kienholz studio, and that, for that matter, all the work dating back to their initial meeting, in 1972, was to be similarly considered retroactively cosigned.

Some critics point to a certain softening in Kienholz's fiercely distinctive production in the years after he met Nancy—some attribute that softening to Nancy herself, others to the fact that Ed himself was at last settling into a happy marriage and a steadily soaring world-class career. On the other hand, the very premise may be tenuous, for some of the late works are easily as viscerally discomfiting, if not more so, as anything that preceded them.

Take "All Have Sinned in Rm. 323," one of the final pieces on the Whitney Retrospective's third floor, the one given over to the years of Ed and Nancy's collaboration. Simply put, what we have here is a lovely, lonesome mannequin, her ratty easy chair scrunched in up close to a flickering TV console, her bathrobe falling open at her shoulders, her naked limbs straddling the set as she flagrantly masturbates herself to orgasm (white lightbulbs course down the insides of her thighs to a lone red one where the legs join beneath her burrowing hand). On top of the set and along the wall behind it are myriad Bibles, images of Jesus, and a large portrait of a lachrymose Tammy Faye Bakker. The title of the piece derives from a tattered sign Kienholz once came upon near a motel on some Idaho back road, that actually turned out to be referring not to Room 323 but rather to Romans 3:23 ("For all alike have sinned and are deprived of the divine splendor and all are justified by God's grace alone"). Kienholz's own notoriously militant "areligiousness" (his word) notwithstanding, the piece is in fact deliciously ambiguous: is it about the woman's abject loneliness or her momentary flooding into splendor? Is it about the prurient way the media and particularly the televangelical media jerk themselves off at the endlessly enticing prospect of human wickedness? (Is it about the way Kienholz himself, nearing the end of his own career, had relentlessly to ratchet up his own righteous indignation at the prospect of such blatant hypocrisy?) Who knows? The point is, lying there spread-eagled, all prone and squirmy, "Rm. 323" is this show's Back Seat Dodge Scandal just waiting to happen ("Paging Dr. Buchanan, Paging Dr. Dole, your presence is urgently requested on the Whitney's third floor").

Only, Nancy Kienholz and the show's superb guest curator, Ed's longtime friend and associate, Walter Hopps, seem keenly aware of just that possibility. So, just off to the side of "Rm. 323," wedged in there in such a way that no photo-opportunity could be contrived that would fail to include it, they've spotted another recent piece, "My Country Tis of Thee," comprising a roundelay of four marching suited-up politicians, naked from the waist down, little flags clutched over their hearts in one hand, their bare right legs firmly planted in a pork barrel, their left hands reaching back to grab, each in turn, the flaccidly drooping member of the marcher immediately behind him.

Indeed, that entire corner of the current installation is like a Venus Fly Trap, just waiting for some latter-day Dorn to stumble in. Thus far, nobody has. Maybe, the infamous NEA troubles notwithstanding, it just takes a hell of a lot more to get a museum shut down (or almost shut down) than it used to.

*

I myself first met Kienholz ten years after the LACMA show, which is to say some twenty {now fifty!} years ago. I'd been dispatched up to northern Idaho, to the lakeside compound where Ed and Nancy had repaired (on a half-yearly basis) some three years earlier, by the UCLA Oral History Program which at the time was compiling a "Group Portrait" of the L.A. art scene. Ed, the notorious reprobate who'd established himself as almost a defining feature of that scene over the previous fifteen years, had abruptly pulled up his Southern Californian stakes in 1973 as his two kids (and Nancy's slightly younger daughter from an earlier marriage) were approaching puberty. He didn't, he said, want them exposed to the city's lax moral environment—the drugs, the casual sex, the permissive street scene.

He himself had fleshed out quite nicely. He was short, though not as short as he seemed, waddling about almost daintily, jauntily heaving a humongous medicine-ball of a belly before him. It was summer and he was usually buck naked except for a pair of shorts or even just underpants, loped rakishly under that proud, round protuberance, which, he repeatedly assured me, was all muscle and no fat—what with the casual way he'd regularly swoop down to hoist some huge metal ingot or other, I wasn't about to argue the point. Seated dubiously for our taped interview sessions, he'd fold his softly sloping (though likewise astonishingly powerful) arms over the top of that bare belly, as if it were a conveniently sited rolltop desk. He was by turns amused, bemused and exasperated with the process, this forced march of recollection. He loved to toy with me, to taunt and test me ("I'm bored," he declared at one point, "let’s go hunting"—or, "Ever been water-skiing? No? Let's all go see what Weschler looks like trailing behind a speed boat.") (Ha-ha.) (Not pretty.) Often the interview sessions bogged down altogether—"You want that story? You're right: It's a good one, damn good. What'll you give me for it?"—into increasingly convoluted sieges of extended bartering. His face was merry, Falstaffian, the goatee filled out and graying, the most startling feature a pair of eyebrows that curled up and up like wafting tendrils of cigarette smoke.

He was in his element—in fact, almost literally so: the compound, by the shores of Lake Pend Oreille outside the hamlet of Hope (technically, actually, in Beyond Hope), was only a few dozen miles from the Depression-era farm, in the hamlet of Fairfield in rural Washington state, upon which he'd been born (or, as he put it, "birthed") and raised and which (rereading the transcripts recently, I find myself realizing all over again) had so decisively shaped him and his aesthetic, which is to say his ethic.

At one point, for instance, we found ourselves talking about the sense of mortality which I'd suggested pervaded much of his work, and he admitted as to how "It may be the farm that I was born and raised on. Because if you pull a breeched-birth calf out of a cow with a small rope around its legs.... When the cow heaves, you pull; you've got your foot braced under its tail, on the flank of her leg, and then the legs of the calf are coming out of her. And it's a hard birth for her because she has to open to allow the rump of the calf to come through. But you reach in, get the calf's tail, get that out, and you pull the calf. You take the mucus off its nose, so it can breathe. It's laying there exhausted; the cow's laying there beside it bellowing and bleeding, but she stands up and starts licking it, gets it up on its feet. So you can have that—you can participate in that miracle, for instance.

"You teach that calf to suck on your fingers so that you can teach it to drink out of a pail rather than suckle the cow; and then you start mixing the milk with the grain in small quantities, and then more and more, until finally it learns to eat grain rather than to drink milk. Then you pasture it and you raise it, and then one day you take a small-bore shotgun and you go out and walk up to it and kill it.

"You jump back and wait a few minutes. You cut its throat and you wait for it to stop twitching (because you can break your leg if it convulses and kicks). You cut its legs off, and you turn it over on its back, and you open it up and take out its innards and start skinning it. And that's meat. That's a realistic process to go through if you eat meat."

I asked him how old he'd been when he'd attended his first breech-birth.

"Oh, I don't know, not that young. I mean, I'm not talking about an early childhood trauma." (Ed never had much patience with my psychologizing tendencies—the world was plenty awful and awesome and awe-inspiring enough without having to have recourse to such half-baked formulae.) "I'm just talking about life on the farm. But I also think that if you eat meat, you should be responsible, or at least acknowledge that. I mean, to have something cellophane-wrapped—you know, on a counter, down at the Farmer's Market—is nice, I guess, as long as you understand that when you buy that, you kill an animal someplace."

Not that Ed was any sort of namby-pamby vegetarian or anything like that—he wolfed veal, for instance, with considerable relish—but he was just a big one for taking responsibility, for acknowledging and never evading the gritty, sinewy, overwhelmingly interconnected sheer facticity of the world: in meat, as in all things.

But in this world always, and never any other. Ed's mother was a devoutly religious Christian, "almost a fanatic," as Ed used to say, in a treacly, Hallmark-homiletic sort of way. She taught Sunday school and regularly (almost compulsively) cast worldly disappointments in the context of other-worldly compensations to come. She fashioned crèches; and she enlisted young Ed in the fashioning of those crèches—his first tableaux. As the years passed, however, Ed would have none of it. One of Ed's first adult tableaux, a sacred complement to its contemporaneously profane "Roxys," was a singularly perverse abstract "Nativity," with a heating-vent-faced Mother Mary (a secret compartment slotted into her rear, for the Immaculate Conception) hovering over a Baby Jesus in his crib (a boxy flashing light from a street barricade, to which tiny kicking doll feet had been suitably affixed) while cuckolded Joseph astride his ass (a stick pony's head erupting from his waist) looked grimly on.

Ed's mother was always deeply proud of her son's eventual worldly achievement, if in perennially deep denial as to its evident purport. Toward the end of his life, when Ed and Nancy embarked on yet another sacrilegious series, this time a suite of crucified Jesus wall figures fashioned out of wagon handles and entitled "76 JCs Led the Big Charade," Ed's mother, still alive and happily ensconced in her own cabin a few hundred yards from her son's lakeside compound, cheerfully welcomed him back into the fold.

Ed's father, by contrast, was a moody, driven, spectacularly competent farmer—a master, beyond the immediate requirements of wheat harvesting and animal husbandry, of virtually all the crafts required for "making do," from carpentry and welding through electrical maintenance and automotive repair and on through every manner of wheeling and dealing—all of which skills he imparted to his son, along with a ferocious work ethic. He was also a deeply frustrated and angry disciplinarian—regularly flogging his boy with a rubber hose (this according to a short piece Ed's adopted sister Shirley contributed to the current catalog), just as he himself had been savagely beaten as a child by his father. ("My brother Ed broke the chain of abuse with his own children," Shirley reports proudly. "He never even spanked them.") Ed never spoke to me of those beatings, except inferentially, recalling "a Turning Point," when he was about fifteen and already quite strong. "One day," he recounted, "my father pushed me too far, and I'd had enough of it. I turned on him, confronted him. And it was the first time I'd ever seen him back down. I don't know whether he backed down because he was afraid of me or whether he realized he was wrong. But he and I had a different relationship after that."

Ed's father, too, was still alive the summer I first went up to Hope to call on the Kienholzes; but, the victim, several years earlier, of a terrible series of strokes, he was little more than a vegetable, unctuously monitored by his nattering wife. And in fact he subsisted like that for another three years, until 1979, a heart-rending spectacle and a horrible prospect, one which haunted Ed profoundly. As he often told his own son, he emphatically did not want to go like that.

*

"From my childhood I mostly remember the isolation," Ed commented one day, "being separate and apart.... I used to sit in the barn and milk the cows and look out through the barn doors and see the aura of the lights above Spokane, which was some forty miles distant, and know that people were not milking cows in Spokane.”

Sometimes when I think about Ed there in the barn, I'm reminded of Marlon Brando's amazing improvised speech in the middle of Last Tango when, after yet another of their passionate couplings, his middle-aged character starts reminiscing for the girl about his teenage years back on a dairy farm and about the time he desperately wanted to go to the dance, was all ready and decked out in his best clothes, his best shoes, but instead his old man forced him to go out and milk the cows, how he got cowshit all over those shoes and was never able completely to rid them of the smell, how humiliating it all was.... Ed told me he grew to so hate milking the cows that clear through to the present day he couldn't abide the sight, let alone the taste of milk.

And indeed, as soon as he'd graduated high school and was therefore able—he was seventeen, and the war was just ending—he bolted. Over the next several years the only constant in his life would be his inability to stay put. He caromed among various small colleges around the Northwest, but none of these stints lasted long. He traveled, racked up a succession of odd jobs—buying cars in Great Falls and driving them to Portland to sell, running a funky bootleg club there, designing liquor displays for Las Vegas storefronts, serving as an orderly at the mental hospital at Medical Lake, Washington (his memories from that experience would form the basis, years later, for his harrowing 1968 tableau, "The State Hospital," and in fact, as he described those days to me during our oral history sessions, he'd sometimes refer to the incidents themselves, and his memories of them, as "tableaux"). He racked up two failed marriages as well, one of which even produced a child, a son, who presently fell out of his life altogether (though, perhaps, this last ought more appropriately to be phrased the other way around). He survived primarily through shrewd wheeling and dealing—and his remarkably self-assured manner and passion for hard bargaining would define essential aspects of his personality to the end of his days. (He always insisted that it was easier for a country boy to come to the big city—get had a few times and get wise—than it would ever be for a city boy to make it in the country. And he enjoyed using me as a case in point.)

It is difficult to trace the precise genesis of Kienholz's artistic vocation. It is not as though there was ever a division between his quotidian life and his artistic production. Just as years later, by the time I met him, Ed's days seemed to be evenly spread between cabin building, tableau constructing, deer hunting, horse riding, art dealing, and, say, car trading, so in the past his artistic activity seemed to have emerged as merely one more emanation of an extraordinarily prolific creativity. (It's worth remembering that for Kienholz a well-turned deal was itself always a work of art.) One thing is clear, however: isolated in the eastern Washington back country, Ed grew to manhood with virtually no exposure to any of the art of the High Tradition. (On one of those teenage junkets back east to Minneapolis—as far east as he'd ever gotten at the time—Kienholz received his first exposure to Rembrandt, courtesy of a visiting show out of the Metropolitan. He didn't know enough to be intimidated. As he recalled the experience for me: "I decided that if the great Rembrandt was that easy....")

Kienholz thus arrived in Los Angeles, one afternoon in 1952 or '53 (the date is uncertain), a brash naïf, and the canvases (or more precisely boards) which he spread across the beveled lawn of a North Hollywood dentist a few days later (this, his first sale, being in fact a trade for the extraction of an impacted molar) were the richly impastoed concoctions of a cultural rustic.

But in L.A. you could get your tooth pulled for one of those things! Ed thought he had died and gone to heaven, and he decided to stay. Across the mid-fifties, steeped in the developing Beat culture, Kienholz began devoting more and more of his time to his art. Living a life of marginal subsistence at best, he scavenged among the back alleys and junkyards of the vast L.A. flatlands, seeking out the materials for his creations. It wasn't so much that he shunned standard artistic materials: he simply couldn't afford them. (On the other hand, the things people threw out in L.A.!) Making do, for example, he'd splash wood boards with paint-soaked brooms, layering the planks with ever more complex arrangements of nailed-on slabs and sticks.

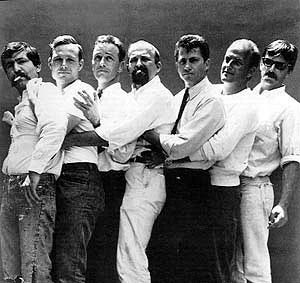

The local art establishment was unimpressed, so Kienholz simply resolved to found his own, establishing a series of makeshift exhibition spaces for himself and his fellow Beat types. His first efforts in this regard, the Now and Coronet Louvre galleries in 1956, transformed the lobbies of two theaters in the La Cienega district. Sales were, well, scattered. But it was through such efforts that Kienholz first came in contact with a strangely intense young college kid named Walter Hopps. Two more different-seeming individuals could hardly be imagined: On the surface, Hopps was skinny, nervous, uptight, with dorky thick-rimmed glasses, but he was incredibly curious and energized and open to all things new (he'd already spent a wonderful apprenticeship burrowed among the remarkable surrealist holdings of Louise and Walter Arensberg—hardly anyone else in town was bothering to visit) and he'd even opened a gallery of his own. "Ed was the first of these tough guy artists," Hopps recalled for me fondly the other day, during a break from installing the show, "who didn't give me shit for being a nerd. He sized me up, probably figured there was something he could get from me (I suppose I was figuring the same way about him), but he immediately put me at ease and we found ways to talk."

Beginning in March 1957, Hopps and Kienholz pooled their resources in founding the now-legendary Ferus Gallery. Kienholz supervised construction of the gallery and subsequently manned the desk in exchange for a long-sought studio space in a back closet; Hopps hustled the administrative side and was in charge of collector-development, such as it was. The first year featured shows of works by members of the Ferus nucleus, including John Altoon, Wallace Berman, John Mason, Craig Kauffman, Billy Al Bengston, Ed Moses

and others, along with such San Francisco sympaticos as Jay DeFeo, Julius Wasserstein and Hassel Smith. They showed Richard Diebenkorn and Clifford Styll, and in the years ahead Ferus would display Kenny Price and Robert Irwin, and for that matter, Giorgio Morandi and Andy Warhol. By that time, however, Kienholz himself would have fallen away. Late in 1958, increasingly dissatisfied with the gallery's increasingly commercial aspect, he sold out his interest to Hopps who subsequently enlisted the entrepreneurial savvy of a transplanted New Yorker named Irving Blum. Though Kienholz continued to show at Ferus even after it moved to much swanker quarters across the street, notably first unveiling that notorious "Roxys" tableau there in 1962 at a black-tie opening night, his continuing disaffection with the gallery's direction brought him to leave in 1963, though he and Hopps remained close through the rest of his life.

It's worth noting how from early on, Kienholz's ethic, his sense of responsibility, as it played itself out in the artworld context, had him, on the one hand, bucking relentlessly against the strictures of market- and critic-driven forces, and yet, on the other, was regularly drawing him back into almost romantic involvement with the fate of young artists and audiences. Around the time of my first visit to Hope, Ed's son Noah came home from high school one day and reported how, when asked what they all wanted to be when they grew up, of the fourteen boys in his class, thirteen (all except him) said they wanted to be truck drivers. This piece of news proved the genesis for the Faith and Charity in Hope Gallery.

Ed built a clean little gallery space, upstairs in the back of his huge studio building, and began parlaying his by-that-time extensive international art world connections for loan shows with which to stock it. The Gallery was open Wednesdays from four to seven in the afternoon during one month each summer—twelve hours a year—but over the years, they managed to bring in shows by the likes of Alberto Giacometti, Francis Bacon, Jasper Johns, Emil Nolde, Sam Francis, and George Rickey. Ed enjoyed sitting there, taking in the reactions of his rustic neighbors and, incidentally, contemplating the remarkable surge in his own life's fortunes (back at Ferus, he'd only been able to slot himself a tiny studio in a virtual closet at the back of the gallery; here the situation was exactly reversed).

Frankly, a second reason Kienholz had felt compelled to abandon his day-to-day responsibilities at Ferus was that his own work was becoming all-consuming, and it was undergoing a marked evolution as well. For one thing, the increasingly three-dimensional wall assemblages were now beginning to leave the wall to stand in their own right as sculpture (although Kienholz would always insist that he himself considered even his most sculptural work to be merely a version of painting): thus, a consistent line of increasingly ambitious development could be traced from those early clap-trap abstractions through "The Medicine Show" and "Conversation Piece" (still on the wall)

through "John Doe" (on a stroller) to "Roxy's" (occupying an entire room), eventually leading toward "The Beanery" and "The State Hospital" (rooms in themselves).

In addition, the purely abstract presentation of the early works was now beginning to clot over with identifiable sociopolitical themes (race relations, sexual politics, the strangulations of Fifties conformity, the prospect of nuclear annihilation and other dire absurdities of the arms race and the Cold War), sometimes conveyed in the most visceral of terms, and often pitched to an ironic tone or joined to sardonic titles (for instance, "They Tarred and Feathered the Angel of Peace," "It Takes Two to Integrate, Cha-Cha-Cha," “The Psycho-Vendetta Case,”

and perhaps most hauntingly "The Future as an Afterthought").

*

Within a few years of his arrival in Los Angeles in the mid-Fifties, Ed married for a third time. Early in 1960, his bride, Mary Lynch, bore him a daughter, Jenny, to be followed, fifteen months later by a son, Noah. But the marital relationship itself was in increasing trouble—Mary was clearly more of a blithe spirit than he was, already an incipient hippie. Something happened—what exactly, Ed would never say ("Any particular series of events that led to your doing that piece?" I innocently asked him. "Yeah," he replied with belligerent finality. "Next question")—and things began falling terribly apart. One night, apparently reeling in his despair over the situation, Ed perpetrated a howling, horrifying freestanding assemblage which he'd subsequently entitle "The Illegal Operation" (in the interim, Hopps had had to momentarily kidnap the piece for safekeeping, fearful that Ed in his grief could destroy it); it would prove the key work, perhaps, of Kienholz's entire career, and arguably one of the seminal masterpieces of latter twentieth century American art.

Its subject, ostensibly, appeared to be a botched back-alley abortion, the woman's body represented by a sagging burlap sack, filled with sagging hardened concrete and trussed to the back of a stripped-down shopping cart, a puncture gash slashing its midriff from out of which poured an oozing slag, a sort of spent life force, a discrete, hopelessly expiring pile. The cart was surrounded by filthy buckets, pots and bedpans which in turn were filled with rusted, dark-stained surgical implements. Off to one side, a naked lightbulb dangled from an arching lampstand, like a hangman's noose; off to the other, uncannily, squatted a pristine dirty-pink cow-milking stool, hastily abandoned, or so, anyway, it seemed. The entire tableau was undergirded and unified by a grungy, circularly spiraling cloth-knitted rug—one last element contributing to the piece's exquisite formal perfection, alternatively drawing the viewer in, vortexlike, or conversely radiating the scene's quiet horror relentlessly outward. Like Wallace Stevens’s jar in Tennessee, the piece seemed to take dominion everywhere. But this was Wallace Stevens as reconceived, say, by Goya.

And yes, it was obviously about an abortion, but it was hardly just a piece of agitprop (as effectively as it may have operated in those terms). In fact, while on some literal level it clearly decried a legal status quo which regularly forced women to such sordid extremities, it could hardly be said to constitute a pro-choice celebration. It was, rather, about all things botched, gashed, and punctured beyond redemption—not least of all, for instance, relationships themselves. Beyond that, Ed's resolute "areligiosity" notwithstanding, the tableau seemed to radiate an almost metaphysical aura: whenever I've happened upon it (as I did once again now at the Whitney), I've found myself being reminded of the Midrashic notion of how "Whosoever destroys a human life, it is as if he had destroyed an entire universe," and beyond that, the Kabbalistic intimation about the calamitous Breaking of the Vessels at the dawn of time, a disaster which preceded and betokened the Fall itself. For his part, while Ed remained firmly reluctant to discuss the piece's specific autobiographical origins, he did aver one day as to how "I'm not sure what Art is—you know, Art, capital A-R-T—and I don't even care a hell of a lot about what Art is, but if there is such a thing as art, and if I ever made a piece of art, 'The Illegal Operation' would be it. That's because it still contains a kind of fury—I'm not sure how you could put emotion in an inanimate object, but that piece has emotion in it, for me and for other people—we bleed off it."

Within a few months of the completion of that piece, Mary and Ed were divorced and, in a highly unusual outcome, especially for those days, Ed had secured custody of the children (initially aged fifteen and thirty months respectively). He was changing diapers, learning how to cook, making beds, carting the kids to the park, bringing them home for their naps (sneaking in a little time in his studio), getting them up and reading to them, playing with them, feeding them dinner, doing the dishes, giving the baths and putting them to bed, at which point, between eight in the evening and two in the morning he'd return to his studio for what may have been, astonishingly, the single most prolifically productive period of his life.

He was fashioning one grittily detailed tableau assemblage after the next, perfecting the technique of plaster casting with which his name would soon come to be inextricably linked, and regularly foraging through back alleys and flea markets and pawn shops for the protean horde with which he was fast populating his ever-expanding room-sized pieces (and also for the busted-up guns and rifles which he'd take home, repair, and then trade with the local dairy man for his kids' daily milk).

Thus, in addition to "The Back Seat Dodge," "The Birthday" now came into the world (a sort of companion piece to "The Illegal Operation," depicting the labor throes of a thoughtlessly abandoned young woman), along with "Visions of Sugar Plums" (the first of what would become a lifelong series of portrayals of married couples locked in sexual impasse, this one with peephole vantages of their separate rictus vantages), "The Wait" (an old widow fashioned out of cowbones, a mangy stuffed cat on her lap, and her lifetime's memories swathed around her neck, jugged in jars like so many pickled preserves),

and, perhaps most famously, "The Beanery," a phenomenally detailed replication, at two-thirds scale, of Barney's, the dark, dilapidated old hang-out, bar, and eatery to which Ed and many of his fellow Ferus colleagues had long enjoyed repairing.

For years Ed had been trying to figure out some way to evoke the eerie, sad squalor of the place, along with its teeming material splendors—the way its more regular denizens retreated into its depths for hours at a time, precisely as a way of killing time—and then one day (August 28, 1964, to be precise), he happened to notice the headline on the Herald Examiner in the untended vending case just outside—"Children Kill Children in Viet Nam Riots" (the paper's other headlines included "Photos Confirm Moon Volcano,” with otherworldly-othertimely illustrations to match, and "Heart Attack Takes Life of Gracie Allen")—and the whole piece came snapping into place in his mind.

For months and months thereafter he carted old bottles and planks and other detritus from Barney's up the sixty-nine steps leading to his Laurel Canyon home (as rural a setting as one could find in the middle of L.A.) and methodically plaster-cast the dozen-plus figures of the bar's time-killing habitués, giving each of them (except Barney) stopped clocks for faces. His children crawled about the emerging emporium as if it were one large playpen. Eventually he had to build rails down the side of his hill to be able to slide the finished piece out.

But these were the pieces that presently formed the core of Kienholz's LACMA show (and Dorn's debacle), an exhibition from which the artist would suddenly emerge quite famous, not to say notorious. (In addition, around this time, he married for a fourth time, a woman named Lyn Shearer, in a union that would last seven years.) Kienholz had a few shows in New York during this period as well, but his attitude toward the art scene there was always prickly and ambivalent at best, and usually just plain surly and resentful (where did they get off imaging themselves the center of the universe, and, as such, why hadn't they acknowledged his contributions a long time ago, just because he happened to hail from out West?). Presently, in any case, he was perfectly content to leapfrog right over New York for the next phase of his career, which was to bring him phenomenal success in Europe. He proved a star at successive Documentas in Kassel, Germany, and in 1970, Pontus Hulten of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm organized a show of eleven of Kienholz's most ambitious tableaux which then went on to tour Amsterdam, Dusseldorf, Paris, Zurich and London—to mounting popular acclaim. Perhaps Kienholz's jaundiced view of the American reality dovetailed particularly well with European perceptions of America in the late Vietnam period. At any rate, most of these tableaux never even made it back to America, instead finding homes, variously, in Amsterdam ("The Beanery"), Stuttgart ("The Birthday"), Paris ("Visions of Sugar Plums"), Cologne ("The Portable War Memorial"), Stockholm ("The State Hospital"), and even Tokyo and presently Milan ("Five Car Stud," Kienholz's shocking 1972 rendition of a black man's gunpoint castration at the hands of a band of masked white bigots). In fact, of the eleven pieces in Hulten's original show, only three ever did make their way back to the United States on a permanent basis: "The Wait" to the Whitney, "Back Seat Dodge" (ironically!) to the L.A. County Museum, and "The Illegal Operation," which is held privately by Ed's dear friends and collectors, Monte and Betty Factor (the former ordinarily keeps it by his dressing room where he gets to confront it every morning) {following their passing, the piece likewise found its way to LACMA}. Thus, one of the great things about the Whitney retrospective is the way it affords for so many of these pieces an (albeit brief) homecoming to the land whose native predicaments originally provoked them in the first place.

PART TWO (What happened next): NEXT WEEK!

* * *

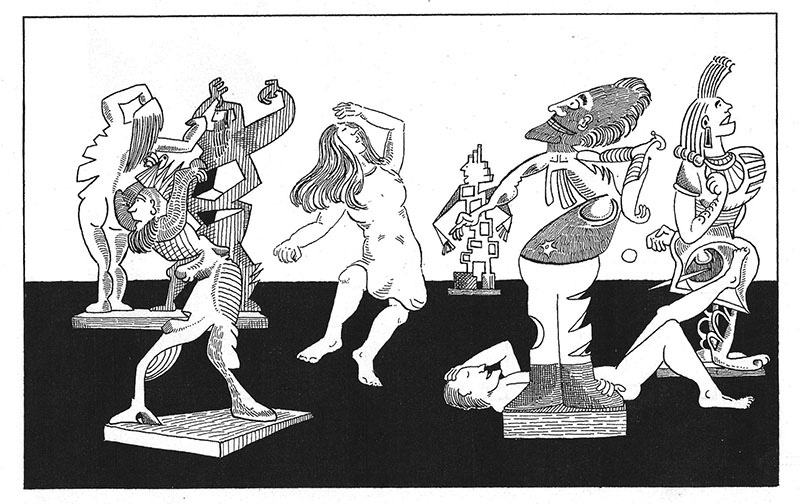

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

animalmitchellpublications@gmail.com

* * *

OR, IF YOU WOULD PREFER TO MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION, CLICK HERE.

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.

A wonderful exampl the Laurel and Hardy/Billie Jean idea is Eggs Tyrone's videos changing the music that people are dancing to: https://www.instagram.com/eggs.tyrone/?hl=en