WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

Welcome

Part one of a two-parter on “Art and Science as Parallel and Divergent Ways of Knowing,” featuring a deep dive into Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson.

***

The Main Event

Back in March of 2011, I was invited to deliver the keynote address for a two-day long symposium in San Francisco, sponsored by the National Science Foundation and curated by the Exploratorium, on “Art and Science as Parallel and Divergent Ways of Knowing.” Looking back on the conference program today, I am given to recall how seminal an event the conference went on to prove for many of those in attendance: the whole thing was videotaped but alas the Cro-Magnon interface deployed at the time may be beyond recovery (still, you can get a sense).

For my own part, I continued to deliver iterations of the talk from time to time in other contexts over the years, and the thing kept fractalizing and compounding. When the good folks at the Templeton Foundation asked if they could excerpt portions of current version on their website, it occurred to me that this here Cabinet might be a good place to ventilate the whole thing as it now stands, especially since it manages to gather up some of the principal themes and vantages that have been animating our whole enterprise from the start (the stalwarts among you may even recognize certain verbatim passages from earlier issues). And what better context within which to do so than in the lead-up to our demi-centenary (our fiftieth number)?

So, here goes:

Art and Science as Parallel and Divergent Ways of Knowing

Part One

Perhaps, to begin with, a remark by Nabokov—always a good place to start—who at the time was laying out the requisites for being a good novelist, though, for our purposes we might think of these as the requirements for being fully alive. But listen to him closely, because it’s the opposite of how we usually think of these things: “The true master,” he says, “requires, the precision of a poet and the imagination of a scientist.” The precision of a poet—and the imagination of a scientist.

Keep in mind, of course, that in some precincts, Nabokov was every bit as famous a scientist as he was a writer. A lepidopterist, to be exact, who once surprised his Italian publisher Roberto Calasso by telling him that he’d never been to Venice. “Good Lord,” asked Calasso. “Why ever not?” To which Nabokov answered, self-evidently, “No butterflies.”

Ezra Pound, who liked to insist that poetry should be at least as well written as prose, used to advise young writers (this according to Frank Kermode) “to accept the discipline imposed by Agassiz on his scientific protégés, who had to describe a dead fish over and over till they had it right, as the fish decomposed.”

Or, as Cezanne noted: “You have to hurry if you’re going to see, everything is fast disappearing.”

To return to the subject of poets, though, I often like to start these sorts of talks with what I call the morning prayer. In this instance, two poems. The first coming from Thomas Lynch, the great undertaker poet,

the first poem from his 2012 Walking Papers collection, a poem, as it happens, called “Euclid”:

What sort of morning was Euclid having

when he first considered parallel lines?

Or that business about how things equal

to the same thing are equal to each other?

Who’s to know what the day has in it?

This morning Burt took it into his mind

to make a longbow out of Osage orange

and went on eBay to find the cow horns

from which to fashion the tips of the thing.

You better have something to pass the time,

he says, stirring his coffee, smiling.

And Murray is carving a model truck

from a block of walnut he found downstairs.

Whittling away he thinks of the years

he drove between Detroit and Buffalo

delivering parts for General Motors.

Might he have nursed theorems on lines and dots

or the properties of triangles or

the congruence of adjacent angles?

Or clearing customs at Niagara Falls,

arrived at some insight on wholes and parts

or an axiom involving radii

and the making of circles, how distance

from a center point can be both increased

endlessly and endlessly split—a mystery

whereby the local and the global share

the same vexations and geometry?

Possibly this is where God comes into it,

who breathed the common notion of coincidence

into the brain of that Alexandrian

over breakfast twenty-three centuries back,

who glimpsed for a moment that morning the sense

it all made: life, killing time, the elements,

the dots and lines and angles of connection—

an egg’s shell opened with a spoon, the sun’s

connivance with the moon’s decline, Sophia

the maidservant pouring juice; everything,

everything coincides, the arc of memory,

her fine parabolas, the bend of a bow,

the curve of the earth, the turn in the road.

Sophie the maidservant, as in Sophia, the Hellenistic/Alexandrine personification of Wisdom, although, myself, I like to think of her as pouring milk, and for that matter, to think of Lynch himself having had something quite like Vermeer’s Milkmaid in mind.

Which in turn brings me to a marvelous poem by Wislawa Szymborska,

the great Polish Nobel-prize-winning poet (as translated in this instance by Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanaugh):

Maybe all this...

By which she means All This—this hall, those chandeliers, that screen, this podium, me, all of you, this whole building, this city, that bay, the entire surround, all of it...

Maybe all this

is happening in some lab?

Under one lamp by day

and billions by night?

Maybe we’re experimental generations?

Poured from one vial to the next,

shaken in test tubes,

not scrutinized by eyes alone,

each of us separately

plucked up by tweezers in the end?Or maybe it’s more like this:

No interference?

The changes occur on their own

according to plan?

The graph’s needle slowly etches

its predictable zigzags?Maybe thus far we haven’t been of much interest?

The control monitors aren’t usually plugged in?

Only for wars, preferably large ones,

for the odd ascent above our clump of Earth,

for major migrations from point A to point B?Maybe just the opposite:

They’ve got a taste for trivia up there?

Look! on the big screen a little girl

is sewing a button on her sleeve.

The radar shrieks,

the staff comes at a run.

What a darling little being

with its tiny heart beating inside it!

How sweet, its solemn

threading of the needle!

Someone cries enraptured:

Quick, get the Boss,

tell him he’s got to see this for himself!

For surely here the image Szymborska must have in mind, the image of the girl spread up there across the big screen, must be very like Vermeer’s Lacemaker. (“In my dreams,” she had recorded elsewhere, “I paint like Vermeer of Delft.”)

And one of the most remarkable things about that painting, in turn, is the way that everything in it is slightly out of focus. Either too close or too far, except for the very thing the girl herself is focusing upon: The two strands of gossamer-thin thread pulled taut in her hands, the locus of all her labors, that little V of concentration. Indeed, the painting is all about concentration: gradually, in-spiringly, we come to concentrate on the very thing the girl herself is concentrating on, everything else receding to the periphery of our awareness. Like nothing else so much as a painter—or in this context, we might say, a scientist—lavishing his or her entire attention on his subject. Or else perhaps what happens as we ourselves pause, dumbstruck, before this canvas in the midst of our museum walk.

Are we perhaps exaggerating here? Look more closely at the threads themselves:

They arrange themselves, as I say, into that crisp, tight V, couched in the M-like cast of light playing upon the hand and figure behind them. The girl, God-like, momentarily focuses all her attention upon VM: the very author of her existence! And hence back to the poem, for the girl threading her needle, the little darling being with its tiny heart beating inside, is of course none other than the poet herself, intent over her scribbled page, laboring toward that perfected line—or else subsequently, perhaps us, her readers, hunched over her completed poem. Though, as the creator of the poem, Szymborska is of course also simultaneously the Boss, as we, too, the readers get momentarily to be, recreating, recapitulating her epiphanic insight, seeing it cleanly for ourselves.

Indeed, Szymborska gets it just right. How in the perfected work of art, be it a poem or a painting—or, I would argue, an experiment and its conclusion—across that endlessly extended split-second of concentrated attention, artist and audience alike partake of a doubled awareness: The expansive vantage, lucidly equipoised, of God; the concentrated experience, meltingly empathic, of his most humble subject.

So I want to begin by talking about absorption, about concentration. The moment, as Leo Steinberg says somewhere, “when the artist stops asking, What can I do? and starts asking, What can Art do?” I imagine that's similar with scientists, too: What is the World doing? Or with Diderot, noting how “painting is best when the artist steps back slack-jawed before his creation”—Diderot, who also said that the artist is merely the first observer of the completed work. Which is to say, that moment when he stops being the creator and suddenly becomes the slack-jawed witness.

Surely, there, too, it must be the same with scientists. I recently read somewhere how Elizabeth Bishop told her first biographer, Anne Stevenson, that she admired “the beautiful solid case being built up out of his ‘heroic observations’ by Charles Darwin,” going on to say that “what one seems to want in art, in experiencing it, is the same thing that is necessary for its creation: a self-forgetful, perfectly useless concentration.”

For, of course, the whole distinction between art and science is of relatively recent vintage.

Indeed, at the New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU, which I used to head, we still considered the sciences an integral part, indeed one of the crown jewels, of the humanities—as would have any Renaissance magus. We did a lot of programming of scientific things, which by the way could get extremely interesting. For example, we used to love having Tom Eisner, the late great entomologist, come down from his aerie up at Cornell to give talks about his wonderful menagerie of weird insects—cockroaches, bombardier beetles, rattle-box moths, flatid plant-hoppers, wolf spiders, and the like. And it turned out that the people who especially loved coming to those talks were the science students, all of whom seemed to be stuck in their ever-tapering silos, burrowing deeper and deeper into one little tiny corner of the genome, spending their entire research life on this one little tiny kink in the chromosome, and here they got to see an entire cockroach! For them, cockroaches were the humanities.

But of course, as I say, this is all a very recent distinction. Not that many years ago, in the Age of Wonder of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, aristocrats would vie with one another gathering together wondercabinets, such as this one here,

more or less following Francis Bacon's prescription for the essential apparatus of “a compleat learned gentleman,” from 1594, when he said that such a gentleman should attempt “to achieve within a small compass a model of the universal made private.” Any such would-be magus would certainly want to compile, in Bacon's words,

a goodly huge cabinet, wherein whatsoever the hand of man by exquisite art or engine hath made rare in stuff, form or motion; whatsoever singularity, chance, and the shuffle of things hath produced; whatsoever Nature hath wrought in things that want life and may be kept; shall be sorted and included.

And you'll notice how in this particular wondercabinet you indeed do have various sorts of scientific apparatus, you have horns and coral and insects, and you have paintings. A good many of the Dürers we now come upon at museums began their lives in cabinets such as this, right alongside the shells and the antlers and the skulls. All of them constituting occasions for marvel at the splendors, the richness, the bounty of Creation (the artist’s efforts being merely a token, an instance, a shadow of the greater Creator’s). And all of this occurring under the sign of absorption and concentration—what I call “pillow of air” moments, where suddenly you notice that a pillow of air has gotten lodged in your mouth and you haven't so much as breathed in ten seconds.

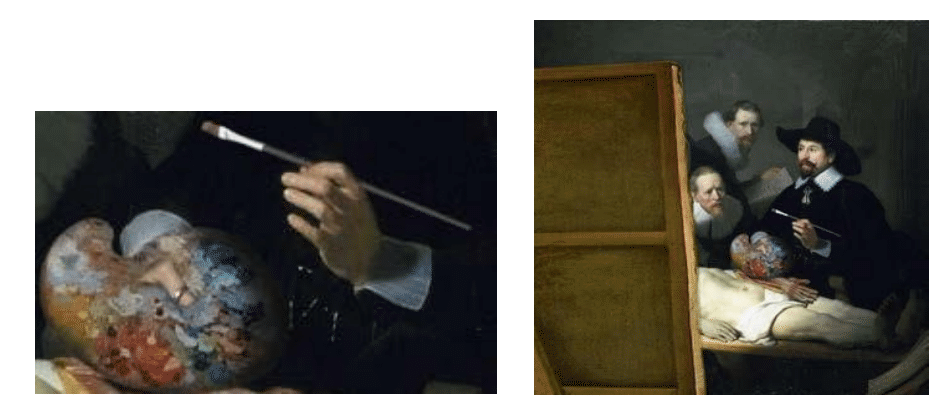

One could likewise cite the examples of Leonardo or Michelangelo, who would never have understood a distinction between their artistic and their scientific practices. After all, the entire field of anatomy, before it split off to become a scientific discipline, was deeply imbricated in artistic practice, culminating of course in the most famous painting of this genre, Rembrandt's Anatomy Lesson:

I just want to stop for a few moments to look at this painting which you've all seen a thousand times, but perhaps to look at it a bit more carefully. The year is 1632, and this is the anatomy lesson of Professor Nicolaes Tulp, the most eminent anatomist in Amsterdam at the time. Rembrandt in a sense is not yet “Rembrandt,” the one we will come to know and revere over the coming centuries.

He is only 26 years old and has more or less just arrived in town from Leiden; and with this painting, he is effectively putting out his shingle as a portrait painter. In compositional terms, Rembrandt is portraying the professor; a cadaver (who is incidentally a recently executed thief, we even know his name, but that’s another lecture) with his arm flayed (the arm being the member with which he would have stolen the thing for whose theft he had been executed, a cloak not unlike the professor’s very own); and six of the professor’s onlooking students. Granted, the final painting includes seven onlookers, but it’s fairly obvious that that guy over there to the far left came late and demanded to be put in...Or at any rate insisted on inserting himself into the commission at a late stage...Maybe forked over his share of the money late, after everyone else had agreed on the terms of the arrangement...And Rembrandt said, “Okay, you get in, too, but we’ll put you way over here.” (And the guy’s even portrayed as a sort of clueless doofus.)

The point is the entire composition is a fiction and would have been understood as such by contemporary observers: it is not a snapshot, as it were, intended to be read as the exact recording of a specific moment in time (chemical photography had not yet been invented: nobody could or would even have imagined such a thing). It recalls an event—that day’s anatomy lesson—but everyone would realize that the artist, who in all likelihood was present at the lesson, in addition would have held a series of separate sessions with each of the individual sitters, and then constructed a scene, posing each one in a different posture, frozen with a different aspect (across the length of the actual anatomy lesson itself, of course, each of them would have moved through a whole range of such aspects, Rembrandt would doubtless have sketched all sorts of ideas, but it was only after the fact that he’d have plotted out this particular iteration).

There are all sorts of other things we could say about the cadaver and the way it is portrayed—how the corpse’s presentation, naked except for the sheet covering its midriff, recalls and no doubt intentionally alludes to images of Christ after he’d been deposed from the cross (Mantegna’s and the like)—Christ who after all had himself been crucified, flanked by a pair of common thieves.

Or about the flayed arm, which is unusual, since in virtually every other anatomy lesson painting or engraving from the period (and there is a whole genre of such images), the part of the body that is portrayed as having been opened out is the part that in fact always was the section first opened in such procedures, which is to say, the belly, the bowels: the part that needed most immediately to be addressed since it would have been the first to start rotting in that era before refrigeration. It has been noted that the arm, flayed like that, likely alludes to the portrait which a hundred years earlier the eminent illustrator Jan van Calcar had offered as frontispiece to the great Andreas Vesalius’s seminal work on human anatomy, De humani corpora fabricus.

(Some commentators suggest that Professor Tulp would have asked to be portrayed in this fashion as a subtle way of identifying himself as the great Vesalius’s true heir, or that Rembrandt might have been currying favor with the Professor or other possible future clients in advancing this sort of suggestion, or else that Rembrandt might have been casting himself as van Calcar’s true heir, van Calcar having himself been a student of Titian’s).

But I want to focus on something else for a moment, or more precisely to have you focus on something else. Because let’s try an experiment: everyone, close your eyes. You’ve all seen this picture a hundred times but I’m curious how you remember it. As you will recall, there’s the corpse, the professor, that doofus off to the left (who we will henceforth bracket out of this conversation), and then the six onlookers ranged, as it were, in two groups, an outer trio, and the inner trio. And those three inner students are gazing intently, awestruck, dumbfounded, at something. But at what?

Now, if you’re like me, you will likely recall them gazing at the flayed arm in hushed, almost queasy astonishment. But—now open your eyes again, and you will see that they are not. Nor, incidentally, are they gazing, as countless academic exegeses of this painting have maintained, at the opened book over there way to the right—the book supposedly standing in for the weight of tradition, or the customary protocols of practice, or whatever. A book’s being the sort of thing an academic book writer might indeed like to imagine they were looking at, but it’s obviously not. No, they're looking at the professor’s hand.

The professor is saying, “With these muscles here—do you want to see something really amazing?—you can do this.” You can rotate your arm in this fashion. And they are looking at that as if they have never seen anything like it. And indeed, never before have they seen it in this way. Actually when you look at the painting closely (as you can the next time you are in The Hague at the Mauritshuis where it resides, a room over from Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl), one of the things that's really interesting is the way that guy in the middle, the goateed fellow craning out over the corpse’s head, has one eye looking at the flayed arm and the other looking at the professor’s. And it's like a movie: up down, up down.

The point, though, is that this is not a painting about death. It's a painting about life. And specifically about two of the most astonishing aspects of human life: manipulability and vision: hand and eye. About the ability to move one’s hand and the ability to see. In other words, about painting: the capacities that specifically make painting possible. A point further reinforced when we now look at the other three onlookers, the so-called outliers. For what are they gazing at? At us, yes. Or at the audience—and there was an audience, these dissections often took place before an audience of variously distinguished guests, as we know did this one. But if you think about it, what they are actually looking at (within the fictional terms of this painting) is Rembrandt himself painting: the painter, his canvas perpendicular to the scene so he can take it all in, gazing at them gazing at him, expertly wielding his brush with his arm, by way of the very muscles the professor is describing.

And those onlookers in turn are no less dumbfounded by the miracle of what is transpiring before them. They are, as we say, getting it.

I mention all of this stuff about looking because one of the things that connects art and science—the practice of the artist with the practice of the scientist—is that moment that goes, “Oh, I see.” I get it. That's what the scientist says when he or she finally figures something out. I see. The veils, we say, fall from their eyes. They are vouched a fresh perspective. (Although it’s worth noting how Isaac Asimov further refines our understanding of the process by noting how “The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds a new discovery, is not Eureka but rather, ‘Hunh, that’s funny.’”) What scientists are striving after is what artists are doing all that time. David Bohm, the physicist, says that “Physics is a form of insight and hence a form of art.” Einstein always claimed that imagination was more important than knowledge (though Mark Twain had earlier noted that “You can’t depend on your eyes if your imagination is out of focus”). Leonard Shlain has written a book about art and physics in which he charts how, time and again, the artists were out in front of the scientists. For example, how Giotto was working on conic sections and ellipses long before Kepler. Or the ways in which Manet and Monet and Cezanne were playing with compressions of time and space—the plasticity of time and space—decades before Einstein.

One last thing about the flayed arm, though, before we move on, because it seems to me—and it has seemed to others—that in addition to all of the above, by way of that hand and arm, Rembrandt is making a conspicuous allusion to Michelangelo, and specifically to the way the newly born Adam reaches out to God with his extended hand in the famous image in the Sistine Chapel.

Which in turn reminds me of those neurological writers who have pointed out that Michelangelo’s Sistine God, in turn, was enveloped in a surround of cherubs and puffed-out drapes that bore a conspicuous likeness to the very brains with which anatomist Michelangelo would have been so familiar:

All of which I only mention because now that we look at his Anatomy Lesson once again, Rembrandt also seems to have included a subliminal allusion to the interior of a human skull in the way he lit the scene in general (the cranial shape of the fade from light to darkness—once again excluding the doofus off to the far left side—such that the professor’s face almost reads as the eye socket, his shoulder as the nasal cleft, the corpse’s legs as the jawbone):

Having said all of that, there's one other thing that's important about this specific painting. As I’ve mentioned, such dissections would have taken place in public theaters. Special guests would have been invited to come. And although quite common in Leiden (from where, incidentally, Rembrandt had only just arrived), they were relatively rare in Amsterdam. We even know the date in this particular instance, for it was a fairly unusual occurrence and it was recorded in public records, January 16th, 1632. And it's almost certain that there in the room—or such at any rate is the contention of W.G. Sebald in the opening chapters of his magisterial The Rings of Saturn—Dr. Tulp’s students would have been gazing out past Rembrandt at, among others, an anatomy-besotted exile, then resident in Amsterdam, named René Descartes.

Sebald convincingly argues that Descartes would not have dreamed of missing the event. And Descartes is important because, only a few years later, in 1637, he would be publishing both his Discourse on Method and his Geometry, with The Meditations on First Philosophy coming only a few years after that, in 1641. And that body of work constitutes, arguably, one of the places where you begin to see the break, the delamination, between the humanities and the sciences, as modernly understood. Not only by way of the mind/body split that comes with Descartes’s dualistic conception (the body no longer conceived of as seat of the soul but rather almost as a robotic automaton, and subject to study as such): “I regard the body as a machine, so built, put together of bone nerve muscle vein blood and skin, that still although it had no mind it would not fail to move in all the same ways as at present, since it does not move by direction of its will or mind but only by arrangement of its organs” (exactly the sort of thing Tulp had been demonstrating with the muscles in the flayed arm). But also with his analytic geometry, with its seminal crucifoid grid of X and Y axes, which would come to allow for the quantitative analysis of all sorts of properties which were once deemed exclusively qualitative. And indeed, you begin to have this split in ways of knowing which will get wider and wider as the years go by, with calculus itself being invented (or discovered) virtually simultaneously by Newton and Leibniz, only a few decades after that, in the 1680s.

Oliver Sacks, once discussing this moment in European intellectual history in a lecture evocatively titled “The Neurology of the Soul,” concluded by insisting that

The Cartesian notion of man as a machine is tremendously powerful, and indeed was absolutely necessary for the rise of an empirical, objective science.

But it is not enough.

It cannot tell us about the personal, the “I,” inside the physiological.

A purely physiological explanation offends common sense and one’s own egotism. Mechanistic neurology needs to be complemented by an existential neurology—of face, internal landscape, Individual.

Until we achieve such a conjunction, we can never hope to fathom the mysteries of perception and action but will remain lost in the empty labyrinths of empiricism.

We need, if it’s not a contradiction in terms, a science of the individual, or at very least one that does not do violence to the individual.

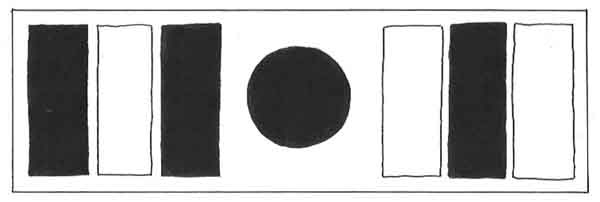

All of which (but especially the discovery of the calculus) puts me in mind of one of my most treasured formulations—people who know me get bored with it, but I can't help but share it with you here in this context. One of my all-time favorite metaphors was provided by Nicholas of Cusa (1401-64) who was a late medieval jurist, astronomer, diplomat, the archbishop of Cologne, and a mathematician, and in that final capacity something of a number mystic. His great masterpiece in that latter regard was called Learned Ignorance (scientists, take note: Einstein would have savored such a title, perhaps he did). At any rate, at one point Nicholas, a good neoplatonist, was engaged in a sort of argument with Aquinas (from over a century earlier) and his followers about ways of getting to knowledge of the whole, which was to say, in those days, knowledge of God. Aquinas, a good Aristotelian, seemed to take the position (granted we are way oversimplifying here) that if you just catalogued everything—if you composed a book on botany, a book on zoology, a book on ethics, on astronomy, and so forth, which is to say to the extent that you were able to, you endeavored to catalog all of Creation—you would eventually achieve knowledge of God the Creator. But Nicholas, for his part, suggested that surely it couldn’t be quite like that. Imagine, he challenged his readers, a circle with an n-sided regular polygon inside. Say, an equilateral triangle. Add a side and you get a square. Add another side and you get a pentagon. Keep adding sides and eventually you get a million-sided polygon.

Granted, at some point it starts looking more and more like its surrounding circle—here he was anticipating the calculus by over two centuries. But in a profound sense, Nicholas went on to argue, that compounding figure would have been getting less and less like a circle. For that thing has a million sides, whereas a circle has only one. That thing has a million angles, and a circle has none. At some point, he argued, you were going to have to make a leap—and he coined the phrase, the leap of faith (Kierkegaard got it from him)—from the chord to the arc. A leap which in turn could only be accomplished in grace, for free. And those would constitute two essentially different ways of knowing. I've always liked that formulation as a writer. You keep piling on detail after detail, and somehow the thing just doesn’t come together, which you can tell, because when you tap it, it just doesn’t ring true. But then suddenly, almost unaccountably, it pops into shape. There’s all that work, which was preparation, preparation as it were for receptivity, but when things finally come together they seem to come together of their own accord. I wonder how much that too is like the work, the practice, of science.

Next issue: Part Two

* * *

A CONVERGENT POSTSCRIPT

Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson has of course been subject to all sorts of pastiches and parodies over the years, but this might be a good place to steer notice to at least two of the most remarkable, the first an exceptionally vigorous slapdash rendition, circa 1856, by a young Manet (who’d have been just about the same age as Rembrandt when he’d fashioned the original),

and the second a more recent effort by China’s celebrated vegetable artist, Ju Duoqi, Bejing’s distaff Arcimboldo

Fascinating the way that both of their knock-offs still evince many of the themes we had been looking at above—the splay of gazes, the centrality of the professor’s hand, the subliminal skull backdrop, and even the de-tropitude of the doofus interloper on the far left.

For her part, Ju Duoqi, who originally sliced and diced her way to fame, starting around 2006, with a brace of similarly startling photocollages based on works by everyone from Gericault, David, and Delacroix, back to Botticelli and Leonardo and forward to Chagall, Picasso, and Warhol, has more recently been making a strong play to become the vegan Yuskavage.

May the interpenetrations of art and science never cease.

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

* * *

NEXT ISSUE

Part Two of “Art and Science,” featuring guest turns by both Robert Irwin and David Hockney.

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.

"Se non e VERO, e ben TROVATO!" - as we Italians often say, when an author, art-analyst, with huge imagination, etcetera, is carried away too much...

Tuo amico,

Giovanni Sogliani di Spalato, Dalmatia, Croatia

Thank you for this! Looking forward to Part II