October 17, 2024 : Issue #78

WONDERCABINET : Lawrence Weschler’s Fortnightly Compendium of the Miscellaneous Diverse

WELCOME

The late, great Oliver Sacks seems to be bursting out all over recently, so why not here as well, by way of Cryptomnesia and Tourette’s—along with a further brace of Errol Morris ads.

* * *

SACKSIANA

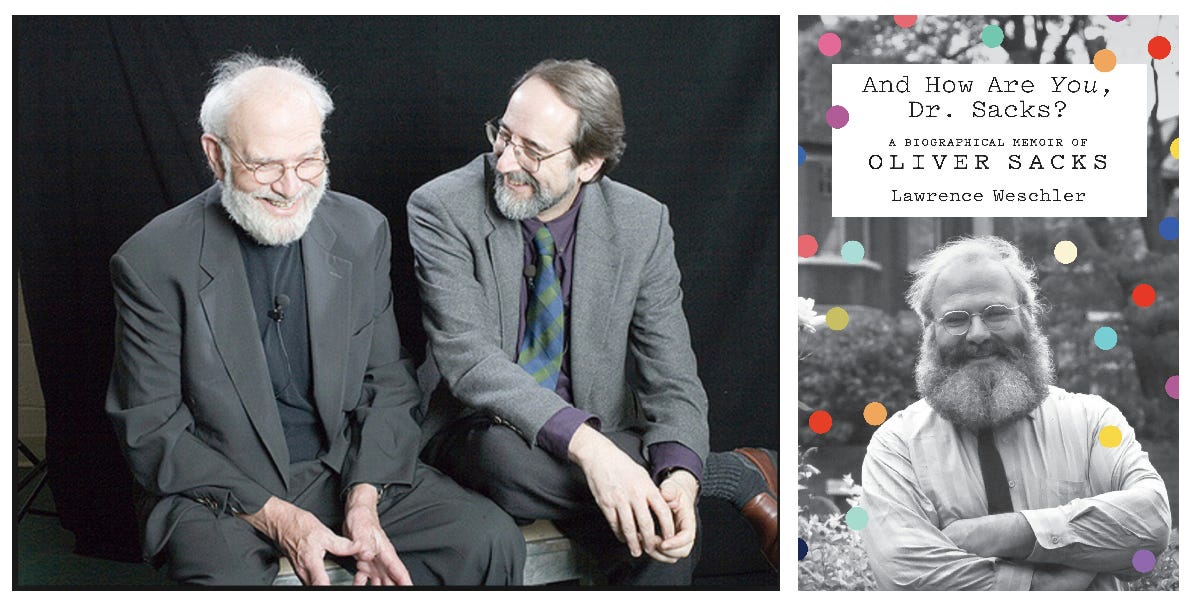

My old neurologist pal, the late Oliver Sacks (subject of my 2019 biographical memoir And How Are You, Doctor Sacks?) has been much in the news recently: his papers having landed at the New York Public Library; the imminent release of his Selected Letters; a new TV series (Brilliant Minds) based in part on Oliver and fictionalized amalgams of several of his case histories (in the series, the lead, played by Zachary Quinto, goes by the name of Dr. Oliver Wolf, “Wolf” having been Oliver’s middle name, and like Oliver, zips around leather-clad on a souped-up motorcycle while suffering from advanced cases of both face-blindness and repressed homosexuality) which has taken to airing on NBC; Ric Burns’s 2020 documentary Oliver Sacks: His Own Life (in which I myself played a substantial role) getting a sporadic rerelease, as for example here at the Yonkers Film Festival, in part to make up for its original theatrical release’s having been upended by early Covid; and so forth.

The Main Event

From the Archives

A Curious Case of Cryptomnesia

Anyway, all of this had me looking back over some old back files and I came upon an extended section from the original manuscript of my own 2019 book which I’d excised at the time but which in turn has taken on renewed interest for me because of a recent theatrical production of the Brian Friel play in question, of which more anon, here in New York.

And I thought some of you might find the entire story of more than passing interest (some others may also recognize an earlier reference to same from back in the “All That is Solid: Typology of Convergences” series from the early days of the Cabinet). At any rate, here it is:

*

In October 1994 there occurred a brief squall of an incident which I’d pretty much forgotten till I found the following memo in my files, addressed by me to the New Yorker’s editor Tina Brown and several of the other subeditors there:

*

TO: Tina, Robert V., John B.,

FROM: Ren

RE: A brewing literary scandal from within our own pages

October 16, 1994

We're facing a curious and potentially ugly literary scandal--although one which I hope will be resolved within the next few days to everyone's satisfaction--one which in any case we will want to be keeping on top of and may even want to cover in some way.

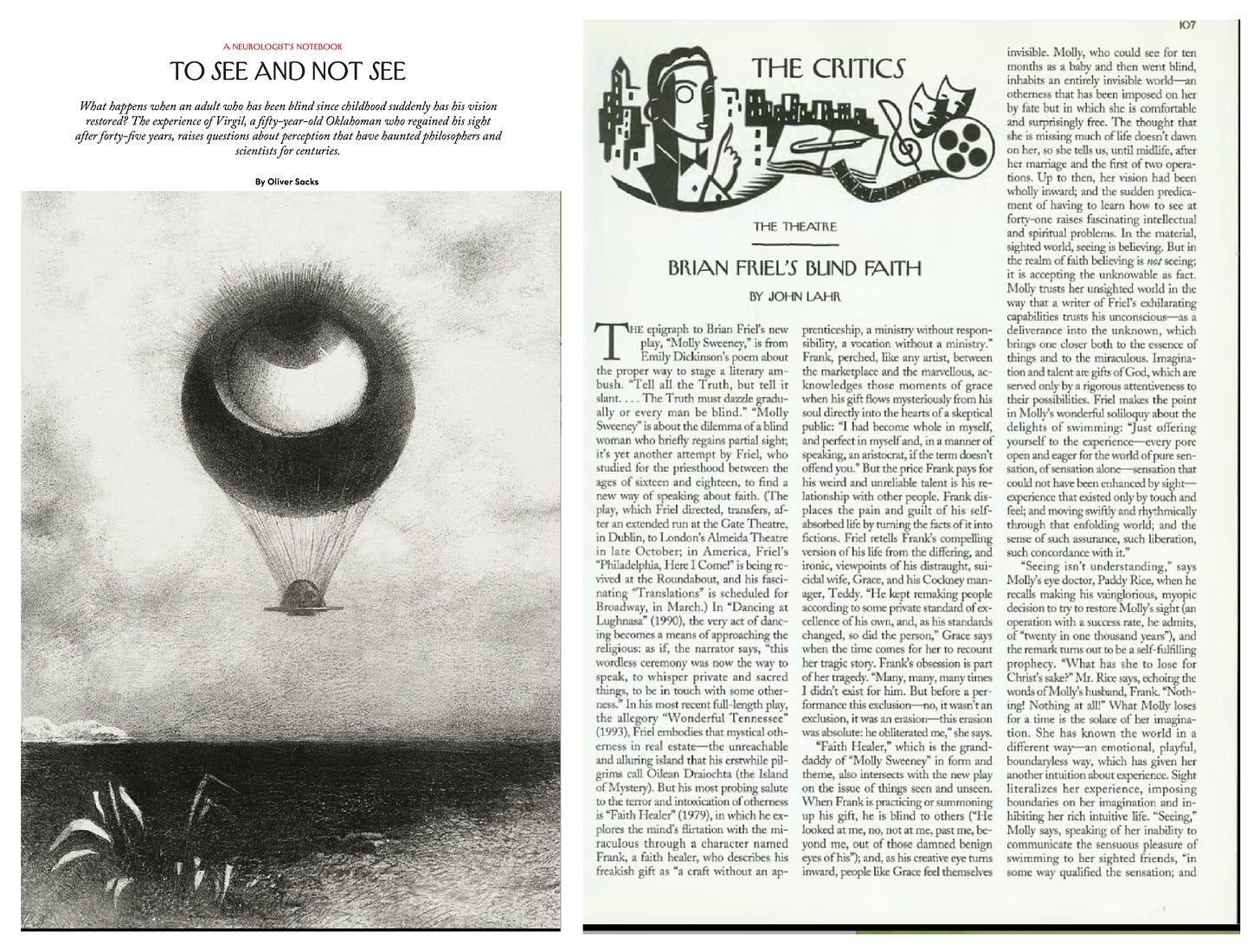

At the end of last week, Oliver Sacks happened to read John Lahr's review of Brian Friel's new play, “Molly Sweeney” in our last issue and was simultaneously unnerved: a) by the play's seemingly uncanny resonances off of his own "To See and Not See" piece, originally published in our own pages last year (May 10, 1993); and b) by the fact that no one from our side had been similarly bothered and at least alerted him to the potential conflict. (I assured him that in all likelihood John Lahr at any rate had never read his piece, etc.)

A few hours later, he independently received a packet in the mail from his pal Peter Brook (adapter, incidentally, of his Man Who Mistook His Wife book in the recent stage piece "The Man Who"), who was sending him a remarkable play which he, Brook, thought he, Oliver, would find intriguing—this was of course the book version of Friel's play. Oliver's initial misgivings were amplified considerably as he read through the play—see below.

Oliver's piece, as you will recall, concerned a blind masseur, employed by a health club, an individual who'd gone blind in infancy following a bout of meningitis but who'd in the years since seemingly achieved a measure of equilibrium with regard to that blindness, but whose spouse and somewhat messianic doctor both contrive to force the blind protagonist to accept a surgical intervention which miraculously restores his vision, although with decidedly mixed results—the masseur becomes entirely disoriented (loses his job) and eventually lapses back into a kind of blindsight, a reversion to neurologically inexplicable blindness. All of this happens in the Friel play as well, although the sex of the protagonist has been changed and Friel makes explicit some of the darker judgments regarding the spouse and the doctor that Oliver, understandably, had to keep implicit. Nor are the plot similarities the only ones—several passages of monolog seem lifted almost verbatim from Oliver's text.

Thus, for example:

Sacks: “Examination, I was told, suggested the scars and residues of old disease but no current or active disease process; and this being so, Virgil's vision, such as it was, could be stable for the rest of his life.”

[NYer, p.62]Friel: “There were scars of old disease, too. But..no current active disease process. So that...her vision, however impaired, ought to be stable for the rest of her life.”

[“Molly Sweeney,” p.27]Sacks: “Virgil could still see light and dark, and the direction from which light came, and the shadow of a hand moving in front of his eyes.”

[NYer p.59]Friel: "...she could distinguish light and dark; she could see the direction from which light came; she could detect the shadow of Frank's hand moving in front of her face."

[MS p.17]Sacks: “Virgil told me later that in this first moment he had no idea what he was seeing. There was light, there was movement, there was color, all mixed up, all meaningless, a blur. Then, out of the blur came a voice that said, ‘Well?’ Then, and only then, he said, did he finally realize this chaos of light and shadow was a face—and indeed the face of his surgeon.”

[NYer p.61]Friel: "‘Now, Molly, in your own time. Tell me what you see.’ Nothing. Nothing at all. Then out of the void, a blur; a haze; a body of mist; a confusion of light, colour, movement. It had no meaning. ‘Well?’ he said. ‘Anything? Anything at all?’ I thought: Don't panic; a voice comes from a face; that blur is his face; look at him.“ [MS p.42]

Sacks: “He would pick up details incessantly...but would not be able to synthesize them, to form a complex impression at a glance. This was one reason the cat, visually, was so puzzling; he could see a paw, the nose, the tail, an ear, but could not see all of them together, see the cat as a whole.”

[NYer p.64]Friel: “But Molly's world isn't perceived instantly, comprehensively. She composes a world from a sequence of impressions... What is this object? These are ears. This is a furry body. Those are paws. That is a long tail. Ah, a cat!”

[MS pp.35-6]

And so forth. Believe me, Oliver is not making this up: there are literally dozens of such instances. One of the two epigraphs of the play is taken from Oliver's piece [p.70] where Diderot is quoted to the effect that "Learning to see is not like learning a new language. It's like learning language for the first time." (The other, from Emily Dickinson, begins, uncannily, "Tell all the Truth but tell it / slant—“)

When Oliver contacted Brook to ask whether he, too, hadn't been similarly shocked by the unacknowledged similarities, Brook informed him that, actually, he'd never read or heard about Oliver's "To See and Not See" piece—he'd only thought the Friel play raised all sorts of issues that seemed resonant of Oliver's concerns and therefore might prove of interest to him. As Oliver detailed the coincidences, Brook concurred that this put an entirely different light on things, though he urged Oliver to proceed with caution, as Friel is a major figure and talent, and, as far as he knew, an honorable man, and one might yet hope for an honorable way out of this sorry situation.

Oliver agrees with Brook (and Lahr) that the play is a remarkable and sensitive piece of work. He’s just bothered that nowhere in the program or in the text was there any acknowledgement of the obvious source material, and nor had Friel contacted him before just deciding to adapt it and even stage the play—and nor, incidentally, for that matter had any financial arrangements been arrived at prior to such performances. (Oliver has received several film offers regarding this piece, all of which are now placed in jeopardy—nor, of course are the rights exclusively his, since the protagonists in Oliver's piece actually do exist, would have shared in the now threatened film rights, and might be expected to have some feelings in this regard). In all of this, Oliver was struck by the difference between Friel's behavior in this regard and Harold Pinter's when he mined Awakenings as the source material for his one-act play "A Kind of Alaska." (It may be hoped, likewise, that the Pinter/Sacks arrangements may yet serve as a model for resolving this potential conflict.)

The story goes on. Oliver has dozens of cousins, so it's perhaps not that surprising that one of them turns out to be an agent with the very literary agency that handles Friel's interests. This fellow has been serving informally this weekend as a kind of back channel. Friel's position was defensively piqued: initially he averred that he had never read any piece by Oliver in The New Yorker, though he subsequently amended that to say that, on second thought, he'd of course read or heard about Oliver's piece somewhere but had absorbed many other sources as well, this theme (as Lahr indicates) had been obsessing him for years, he'd already started on this play before Oliver's piece ran, etc.*

FOOTNOTE: It subsequently turned out that over a year earlier, the New Yorker’s editor Tina Brown had had a visiting Brian Friel over as a guest at one of her legendary dinner soirées, and that when conversation turned to the theme of blindness and the restoration of sight which Friel had recently taken to exploring in preparation for a project he was then gestating, Ms Brown mentioned that she had just gotten in a fascinating manuscript on that very subject, subsequently (unbeknownst to Sacks) sending Friel over a copy of the doctor’s typescript. The fact is Friel never did see the piece in its New Yorker format, so the assertion that he must have had understandably failed to jog his memory.

Oliver's cousin-agent conveyed to his client a sense of the extent of the borrowings, and one has the sense, by Sunday night, that a more measured, formal, and one would hope, commodious letter will be forthcoming, from Friel to Sacks direct. There is considerable time pressure because the play will be opening in London next week (and then coming here).

All of which raises the question of what, if anything, we ought to be doing about all of this. I would merely point out that:

1) the original piece did run in our magazine and hence we may ourselves have a legal stake in all this--after all, arguably, we, too, were the ones being plagiarized. (Also: do the actual masseur and his wife and doctor have any cause to feel piqued at us for not sufficiently protecting their interests?)

2) other readers besides Oliver may catch the odd resonances off of Lahr's piece and wonder why we didn't.

3) this is of course a fascinating story in its own right and may eventually merit a follow-up--by Lahr? a Talk piece? etc. (Note: depending on how things develop, Oliver may or may not want such a piece to run, and it seems to me our first allegiance in this matter should be to him and his desires.)

And actually, it is all quite fascinating. I don't for a moment take Friel to be some lazy thief. (As we all know, he is regularly being touted as a Nobel finalist, as for that matter is Oliver.) He's obviously refracted all of this material through the prism of his remarkable dramatic and intellectual sensibility. To what extent he just absorbed those passages and themes in the heat of his creative process and no longer even realized the extent of his borrowings... to what extent (as Peter Brook suggests) it's wonderful the way physicists and artists and playwrights and performers and psychoanalysts and neurologists are all freely borrowing from each other these days... to what extent Sacks is himself a kind of theme-lifter, in the sense that from among all of his myriad actual patients the ones he feels consistently drawn to portray in his studies are those whose cases echo Homer or Andersen or Grimm or Borges, which is to say those that refract the great ur-themes that obsess all artists... well, all of that is worth considering as well.

Anyway. Thought you'd want to know. I will keep you apprised of developments, or you may want to start talking with Oliver or his assistant Kate directly.

*

In the end, I note from a scrawl of marginalia, I didn’t even send this memo to my New Yorker colleagues. Things were apparently moving very quickly, and Oliver asked me not to. The next day Oliver got a fax direct from Friel himself:

Dear Dr. Sacks,

I am writing direct to you because I have learned through my New York agent that you were disquieted by my play MOLLY SWEENEY, and because I felt that a brief background to my writing of the play might reassure you.

Over a decade ago, I wrote a play of monologues called FAITH HEALER—as with MOLLY SWEENEY, a cast of two men and a woman. This, too, is a story about healing and ‘miracle’ cures. In the intervening years, I have always wanted to write a companion piece. In the meantime, too, I developed cataracts in both eyes and that stirred my interest in sight, seeing, vision, etc. Because of that interest I read maybe a dozen texts on the subject, both medical and philosophical—Zehi, Locke, von Senden, Berkeley, Strampelli, Valvo, Scholler, Gregory, etc.; and your own TO SEE AND NOT SEE which sent me to all your published work; and many, many biographies and memoirs by blind people. And indeed, in the first drafts of my new script, the central character owed much to the background and temperament of Richard Gregory’s ‘S.B.,’ the best documented case, as you know. But I switched to a woman because I wanted to set up comparisons with the echoes of Grace Hardy of FAITH HEALER.

But back to your disquiet. Your work was indeed one of the stimuli to explore seeing/vision as a metaphor and indeed suggested a framework within which that exploration might take place (a framework that was becoming more real to me because of my own condition). And for that stimulus I am most grateful. But I must reiterate that the characters in MOLLY SWEENEY are all fictional. If Molly has a ‘real’ antecedent, it is Grace Hardy whose almost identical economic and cultural background she shares. And if any similarities exist between my play and your article, that similarity is altogether unconscious. Indeed, if Molly Sweeney makes a journey similar to your Virgil’s journey—as indeed does ‘S.B.’ and most of Valvo’s case histories—that has to do with the fact that the physiology of their diseases is so similar.

As I have said, I read everything about the disease I could lay my hand on. It did occur to me that perhaps acknowledgment of all those sources of factual information might be made, but I didn’t do that because Molly and the other two characters are totally fictional.

However, because of your disquiet, I have reconsidered my attitude; and if it is important to you, I’d be happy to acknowledge you and all the other sources.

Yours sincerely,

Brian Friel

And in the end, Oliver decided to let matters rest at that: it just wasn’t worth causing more of a scene. On a little posterboard outside the theater at the premiere, (and at all subsequent performances and in the front of the published version of the play thereafter) there was posted a grudging little Author’s Note that read:

Interestingly, the whole affair piqued Oliver’s ongoing interest in cryptomnesia—the historical tendency of writers (and often quite exalted ones) to copy from others, often verbatim, without realizing that they are doing so—a subject to which he would frequently return in later years in his own writings (see especially his piece “Speak Memory” from the February 21, 3013 issue of the New York Review of Books). Still, it is intriguing how often Sacks’s works in particular (not unlike those of Ryszard Kapuscinski) are subject to such unconscious plagiarisms, perhaps in both cases because the works strike such primordial nerves across such hypnotizing rhythms.

*

One wonders if—and if so, how—the folks in the writer’s room over at NBC’s Brilliant Minds might one day choose to layer this curious case, or one vaguely like it, into their ongoing evocation of The World Oliverian. I, for one, will be staying tuned.

* * *

& A FURTHER DELVE INTO THE SACKS-ADJACENT WORLD

During the years I was first getting to know Oliver, in the late seventies and early eighties, he was deeply engrossed by his deep dives into the worlds of individuals beset by Tourette’s Syndrome. Indeed, as was often the case with such explorations of his, in the years to come he would virtually single-handedly be bringing the situation of such people—heretofore quite misunderstood when not outright maligned, if recognized as such at all—to the wider sympathetic imagination of the public at large. I got to know several of his—they weren’t even patients exactly, rather friends and interlocutors, if anything collaborators and fellow spelunkers: the photographer Lowell Handler, for instance, and the sculptor Shane Fistell, among others. Several of them would feature a few years after that in a groundbreaking documentary on the subject, Laurel Chitten’s 1993 Twitch and Shout, and when that film got a showing at the Museum of Modern Art, I myself got to cover the event for The New Yorker’s Talk of the Town.

See the trailer here, and the film itself via Kanopy here.

MOMA WHEN IT'S JERKING

The New Yorker, April 10, 1995, Talk piece

The Museum of Modern Art's relatively arcane "What's Happening?" new-film-and-video series hardly ever sells out, but then, as Laurel Chiten, the producer-director of "Twitch and Shout," a marvellously moving (and improbably funny) new documentary on Tourette's syndrome, told the people at MOMA early on, they just didn't know the Tourette's community. Sure enough, by the time the video's 6 P.M. showtime rolled around one evening several weeks ago, MOMA's Titus 2 auditorium was packed, and the place was jumping. It was hopping and tooting and barking and whooping; it was clicking and clucking and cussing and cursing. Le Tout Tourette was out in force, and the place was jerking.

Today, Tourette's syndrome is understood to be a neuro-behavioral condition—caused by disequilibrium in the person's brain chemistry, usually genetic—but this enlightened awareness is barely a generation old and, in any case, has yet to radiate out to the wider society. Before the mid-seventies, a psychoanalytic model held sway; the convulsive tics and twitches displayed by most Touretters, along with the compulsively explosive and sometimes unbelievably obscene vocalizations, were attributed to neurotic and neurotogenic family patterns. Touretters were stigmatized and even liable to commitment. (They are in fact in no way mad.) Before that, other, still more archly moralizing and theological etiologies were adduced: Tourettic individuals were deemed to be possessed by Satan, and some even ended up being burned at the stake.

Word of the MOMA event had spread along the Tourettic grapevine—specifically, among members of the Tourette Syndrome Association, a support and solidarity group that is itself only a generation old—and, the outside world's prejudices notwithstanding, the hall had taken on the aspect of a liberated territory. There was an antic, carnivalesque quality to the crowd, with whippoorwills of glee rising to the rafters, along with the happiest, most insouciant damn curses you ever did hear.

One fellow was stutter-stepping up a side aisle, compulsively darting lightning-quick little finger jabs at each successive wall panel. A young woman in amiable conversation with her neighbor suddenly blurted out, at the top of her lungs, though to no one in particular, "I have no clothes on, you stupid putz!" and then, without missing a beat, resumed her mild conversational tone, as if nothing had happened. One of the most flamboyant and extravagant ticcers, a shaggily bearded young man in bluejeans and a blue plaid work shirt, sat volubly beside his wife, also a ticcer (though a decidedly milder one), dandling their adorable baby daughter in his lap: he'd bark, curse, wrench his head violently from side to side while his daughter gurgled contentedly, completely oblivious, innocent of tics of any sort.

Not everyone in the audience was so relaxed. Many eyed their watches antsily. (When was this movie going to get started already?) One fellow in particular, a big, gangly guy in a grey sweatshirt, seemed to positively glower at the pandemonium. Every once in a while, he'd steal a swig from a Snapple bottle brimming with an amber liquid that seemed decidedly more potent than iced tea.

Finally, the lights went down, but, as opposed to the usual drill in such circumstances, the encroaching darkness barely stilled the tumult: the auditorium momentarily seemed a midnight-loud frog pond. Onscreen, Lowell Handler, a Tourettic photojournalist, whose peregrinations provide the film with its narrative structure, was shown jerkily navigating his way through a set of airport metal detectors as his voice-over commented on how Tourette's "is a disorder that pushes other people away: what people don't understand, they fear." There followed a quick cavalcade of other Touretters, whose stories would be interleaved through the rest of the film: Chris Jackson, for instance, the masterly guard on the Denver Nuggets (he has meanwhile changed his name to Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf), who is given to a wide medley of yelps and jerks while on the court, but is nevertheless able to overmaster them all in moments of intense concentration (in fact, almost exclusively in such moments)—so much so that he's become one of the league's premier free-throw shooters. Shane Fistell, an intensely soulful James Dean-like Canadian artist, whose tics were the most violently dramatic of anyone's shown in the film (at times he almost seemed a marionette being jerked randomly about by a perverse puppeteer), noted thoughtfully how "People, when they get drunk, they go down the street hollering and picking fights. It may be frowned upon, but it's not unacceptable, it's something that's tolerated by society. Whereas my tics are not tolerated."

All the while, Tourettic members of the audience were popping off. And, just as uncontrollably—and apparently preconsciously—some of the non-Tourettic members of the audience, despite everything being explained to them on the screen, were proving incapable of suppressing their habitual urge to shush their rowdy neighbors: "Sh-h-h!" they'd hiss peremptorily. Some of the Touretters in turn developed "Sh-h-h-ing" tics of their own, and some of these became ejaculations of "Sh-h-it! Shit! Fuckshit, shitfuckshit."

The fellow who seemed to be having the hardest time was the bearded father in the blue plaid shirt. "Goddam motherfucker, unmarried bitch!" he'd yell at the top of his lungs, then rock himself intently, alternately clucking and barking, clucking and clicking, clicking and clicking—like a metronome. At one point, his own image was suddenly up there on the screen. "That's me! That's me!" he whooped. And sympathetic eruptions of "Eric!" "Eric!" "Eric!" eddied about the hall—"Motherfucker!"

"Woof!" Eric took to barking. "Woof...Wwfff." Whereupon the man with the Snapple bottle, a few rows down, suddenly wheeled around and angrily, if somewhat slurringly, demanded, "Dogs outside! Scram! No dogs allowed in here." Within seconds, the two had bounded from their seats and seemed about to come to blows: out of nowhere, they'd become like two dogs on a beach, snarling and cursing, straining at their owners' leashes. And, indeed, other audience members tumbled out of their seats, to pull them apart and escort them, separately, outside, Eric wailing plaintively all the while, "But why should I have to leave? Here of all places! This is supposed to be a Tourette thing!"

Out in the vast foyer a few moments later, Eric, his wife and baby, and some other members of the family huddled in a corner, calming, calming, while the man who'd been drinking stood sheepishly alone over on the other side, weaving, staggering a bit. A few of the Touretters who'd helped escort Eric out of the hall now went over to talk to the loner. After a while he simply left.

"Strange thing," one of the fellows who had been talking to the guy remarked. "Because I'm almost sure that he's a Touretter himself. He acknowledges how sometimes he gets all ticcy, but refuses to see any doctor about it. He drinks to calm himself down—kind of self-medicates. Says he was drinking so much because he was so tense."

"Kind of like an anti-Semitic Jew," someone else surmised. "Or a gay-bashing homosexual. Eric may have flipped the guy out so badly precisely because he presented such an extreme version of what he worries about in himself."

Dr. Leslie Linet, a psychiatrist, who serves as the editor of the Tourette Syndrome Association's newsletter, and who had been listening in, then interjected, emphatically, that Touretters, for all the social scandalousness of their tics and vocalizations, are in fact "in no way more likely to be violent or physically dangerous than anyone else in society." He continued, "Their symptoms are involuntary but not irresistible, in that they can be momentarily channelled aside. An impulse toward personal violence, for example, can be diverted toward an inanimate object. And even in the instance this evening, for all its peculiarities, the thing that's most striking is how, in fact, the two of them didn't come to any actual physical blows."

Eric presently emerged from his corner, and the associations that now came to mind were, if anything, with epilepsy. For he seemed as calm and serene as he'd earlier appeared desperate and racked. He and his family went back into the auditorium for the film's dénouement and were able to join in the rousing ovation that the audience lavished on the filmmakers at its conclusion. Afterward, Ellen Schneider from PBS's "P.O.V." series informed a delighted Laurel Chiten that "Twitch and Shout" was being picked up for nationwide television airing this summer.

Meanwhile, outside again, Eric said that he was eager to get back home to northern Westchester County—that, as usual, the city was giving him the willies. Just crossing the county line into the Bronx, he went on, makes his tics and shouts instantaneously shoot up every time, whereas back home he's contrived all sorts of ways of keeping calm.

Like what?

"Well, like rock climbing," he said, smiling. Smiling and twitching. Twitching and jerking. "I find rock climbing incredibly relaxing. In fact, just this morning, trying to psych myself up for the ride down here, I was out scaling Breakneck Ridge."

* * *

ERROL’S AERIE (cont.)

A few more classic commercials from the Molochy side of documentarian Errol Morris’s protean production (the sort of thing that makes everything else possible).

Levi’s:

Citibank:

Levi’s:

Citibank:

* * *

ANIMAL MITCHELL

Cartoons by David Stanford, from the Animal Mitchell archive

animalmitchellpublications@gmail.com

***

* * *

OR, IF YOU WOULD PREFER TO MAKE A ONE-TIME DONATION, CLICK HERE.

*

Thank you for giving Wondercabinet some of your reading time! We welcome not only your public comments (button above), but also any feedback you may care to send us directly: weschlerswondercabinet@gmail.com.

Here’s a shortcut to the COMPLETE WONDERCABINET ARCHIVE.